Honestly Ask (and Answer) Yourself: Do My Clients Trust Me?

Trust is complicated in many aspects of our daily lives; by comparison, trust in business seems relatively straightforward. Or is it?

Trust is complicated in many aspects of our daily lives; by comparison, trust in business seems relatively straightforward. Or is it?

While personal trust involves emotional and relational complexities, trust in business is not necessarily uncomplicated. It involves navigating ethical dilemmas, managing diverse relationships, adapting to cultural differences, and maintaining transparency—all of which require careful attention and can make trust in business equally, if not more, complex.

Here’s where things are seemingly straightforward in business. We all know it is crucial to have your clients trust you because trust forms an enduring client relationship, driving loyalty and long-term success. When clients trust you, they feel confident in your ability to deliver on promises, provide high-quality services or products, and act in their best interests.

This trust leads to greater client satisfaction, repeat business, and positive word-of-mouth referrals, which are invaluable for sustaining and growing your business. Furthermore, trust facilitates open communication, allowing clients to express their needs and concerns freely. This enables you to address issues promptly and tailor your offerings to meet their expectations more effectively. Again, the straightforward takeaway is higher client satisfaction leads to stronger business relationships.

Conversely, your relationship becomes increasingly complicated if your clients don’t trust you. How can you address the disconnect? First, you must acknowledge that distrust is a factor, which is easier said than done.

Ask Yourself Again: Do Your Clients Trust You?

Whether you call them customers, clients, stakeholders, or partners, the cornerstone of your business’s success is truthfully asking (and answering), “Do these people trust me?”

Most will say yes. Of course they do, or they wouldn’t be working with me. Right?

Not necessarily. In some cases, making a change could lead to significant disruptions in operations, production, or service delivery, which the client may want to avoid.

In others, existing contracts or agreements might legally bind the client to continue the relationship for a specified period. Alternatively, your company might supply critical components or services the client cannot quickly source elsewhere, creating a dependency despite trust issues.

The bottom line is that clients continue relationships with untrustworthy people until they find a suitable replacement or alternative solution. Are you ready to be replaced? Can you afford to be replaced?

Honestly asking and answering if your customers trust you is crucial because it provides a candid assessment of your relationship with them, revealing strengths and areas needing improvement.

Trust is the foundation of customer loyalty and satisfaction, directly impacting repeat business, referrals, and overall reputation. By reflecting on this question, you can identify whether your actions, communication, and service quality align with customer expectations and ethical standards.

Then comes the hard part: Acknowledging trust deficits.

This allows you to take proactive steps to rebuild and strengthen trust through transparency, reliability, and responsiveness. Ultimately, this self-awareness fosters a customer-centric approach, ensuring long-term success and a resilient business built on genuine trust and credibility.

But in our haste to be trustworthy, we often forget one critical variable: people don’t trust those who never take risks. If all we do is be trustworthy and never do the trusting ourselves, we will eventually be considered untrustworthy.

Because to be fully trusted, we need to do a little trusting ourselves.

Examining the Connection Between Risk, Trust & Trustworthiness

We often talk casually about “trust” as if it were a single, unitary phenomenon—like the temperature or a poll. To speak meaningfully of trust, we must declare whether we are talking about trustors or trustees.

- The trustor is the party doing the trusting—the one taking the risk. These are, for the most part, our clients.

- The trustee is the party being trusted—the beneficiary of the decision to trust. This is, for the most part, us.

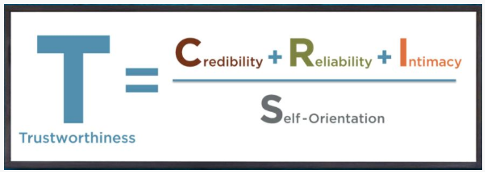

The Trust Equation is a valuable tool for describing trustworthiness:

But where is the risk? In the Trust Equation, the risk appears mainly in the Intimacy variable. For example, many professionals have difficulty expressing empathy because it could make them appear “soft,” unprofessional, or invasive. Of course, it’s that kind of risk that drives trust.

Often, empathy begins with reciprocal pleasantries that help build and strengthen social bonds. Simple gestures like greetings, compliments, and polite conversation create a sense of connection and community.

Pleasantries facilitate communication by opening lines of dialogue, including:

- “I was up late with a sick kiddo and running late. Did I miss anything this morning?”

- “Was that a TikTok reference? I’m usually behind on social media references.”

- “You handled that difficult interaction really well. Better than I probably would have.”

- “Best of luck with your presentation this afternoon. I’m looking forward to attending.”

They serve as a precursor to more meaningful conversations, allowing individuals to gradually gauge each other’s intentions and build trust. Taking small steps, signaling respect and goodwill, shows that we recognize and value the other person, which is fundamental in establishing trust and allows others to reciprocate.

- “Oh, I know all about sick kids and feeling out of sorts the next day.”

- “No idea, but I’m sure someone will show us the video later.”

- “Thank you. I’ve had my share of challenging conversations. I’m sure you would have had a similar response.”

- “Thanks! Hopefully, it will be worth your while!”

This increases intimacy levels, and the trust equation gains a few points. If we don’t take these small steps, the relationship stays in place: pleasant and respectful but stagnant in trust.

While the Intimacy part of the Trust Equation is the most obvious source of risk-taking, it is not the only one.

Here are some ways to take constructive risks in other parts of the Trust Equation:

- Be open about what you don’t know.Although you may think it’s risky to admit ignorance, it increases your credibility if you’re the one putting it forward. Being open about what you don’t know fosters honesty and transparency, builds trust, and encourages collaborative problem-solving.

- Make a stretch commitment.Most of the time, you’re better off doing exactly what you said you’ll do and ensuring you can do what you commit to. But sometimes, you must put your neck out and deliver something fast, new, or different. Never taking such a risk is to say you value your pristine track record over service to your client, and that may be a bad bet. Making a stretch commitment demonstrates ambition and confidence in your abilities, inspiring trust and motivation in yourself and others to achieve challenging goals—even at the risk of failing.

- Have a point of view. If you’re asked for your opinion in a meeting, don’t always say, “I’ll get back to you on that.” Having a point of view rather than an immediate answer is essential because it demonstrates that you have thoughtfully considered the issue. It encourages a more in-depth discussion and collaborative decision-making, ultimately leading to better-informed and more trusted outcomes.

- Try on their shoes. You don’t know what it’s like to be your client. Nor should you pretend to know. Genuine empathy and understanding come from actively listening to their unique experiences and needs rather than making assumptions, which fosters trust and more effective solutions.

While trust always requires a trustor and a trustee, it is not static. The players must occasionally be more elastic in their approach and trade places. If we want others to trust us, we have to trust them.

Resources to Build Your Trust Skills:

- Join or watch a replay of our free webinars.

- Build trust on your terms through our Self-Paced Online Courses.

- Join the crowd and sign up for one of our Public Virtual Workshops.

- Subscribe to our newsletter.

- Follow us on LinkedIn.

- Contact us directly to learn about private workshops.

I’ve often wondered: is our real workplace office the coffee shop?

I’ve often wondered: is our real workplace office the coffee shop?