Trust, a universal concept, is pivotal in our daily conversations. We often invoke it in statements that we believe to be meaningful. It’s a comprehensive language that binds us all, connecting us in our shared understanding of its importance.

However, its meaning becomes blurred when used as:

- “Trust in the airline industry is down.”

- “I don’t trust what media and news organizations say – I rely on people like me for trustworthy information.”

- “I trust Amazon, but not Google.”

While the word trust is omnipresent in each statement, and others like them, the level of discussion about trust is fraught with definitional ambiguity everywhere.

Imprecision in discussing trust is not just a minor inconvenience. It can significantly impede progress in various areas, including personal relationships, business, and societal development. The stakes are high, and the need for clarity is essential and urgent. This urgency underscores the importance of precise trust definitions.

How Clear Definitions of Trust Transform Personal Relationships, Business, and Societal Growth

Trust can sow the seeds of misunderstanding when ambiguously communicated, potentially leading toconflicts. The cumulative effect of misinterpretations, misaligned expectations, and insecurity can lead to a complete breakdown of the relationship. Precise definitions of trust are helpful and necessary for establishing and maintaining strong personal bonds.

In business, imprecision in discussing trust can erode confidence among team members, partners, and clients. For instance, stakeholders may feel deceived if a company vaguely promises transparency but fails to define what that means. Businesses that are not clear and precise about their trust policies can damage their reputation, leading to significant loss of customers and revenue. The potential damage is substantial, and the need for precision is paramount.

For workplace colleagues, trust is not just a nice-to-have in collaboration; it’s a must-have. Imprecise communication about trust can create an environment of doubt and skepticism, making team members reluctant to share ideas or collaborate effectively. However, clear communication is the key to unlocking the full potential of trust in collaboration, empowering us to foster a culture of openness and cooperation.

In societal contexts, the lack of precision in trust discussions can hinder the successful implementation of policies and initiatives. For instance, vague trust-based government policies can lead to public disillusionment and a lack of support for essential programs, thereby hindering societal development.

Meaningful discussions about trust are crucial. They pave the way for valid, justified conclusions and actions. They also play a vital role in fostering trust-based organizations, cultures of trust, and increased trust in institutions. These discussions are essential for understanding and addressing cross-generational trends in trust.

Without standard definitions, we are reduced to bemoaning the fate of trust, wringing our hands as bystanders, accomplishing nothing. We need basic definitions.

Let’s call them:

- the Grammar of trust,

- the Objects of trust, and

- the Actions of trust.

The Grammar of Trust: Trust is a Noun, a Verb, and an Adjective

What does it mean to say, “Trust in the airline industry is down?” Does it mean major airlines have become less trustworthy? Or does it mean public opinion is turning against the airline industry? Or both?

It matters if our discussions are to have any policy implications. This is loose language, meaning nothing unless we clarify our definition of trust.

- Trust, as a noun, is the state of a relationship between two parties. It exists or doesn’t; if it does, it is described as high or low, thick or thin, broad or deep. Sociologists use this to talk about high- or low-trust societies or cultures. In business, Edelman’s Trust Barometer primarily (when it is clear) focuses on the state of trust.

- To trust someoneis to take a risk, to willingly put yourself in harm’s way of another. This is the verb “to trust.” Psychologists focus on this propensity to trust, the entry point of business books like Bob Hurley’s The Decision to Trust.

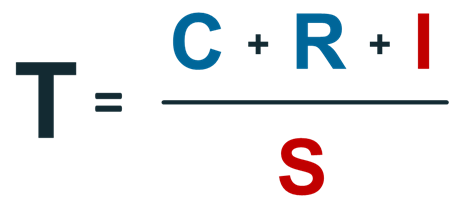

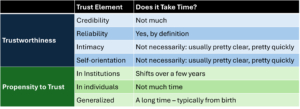

- Trustworthinessis an adjective, an attribute we ascribe to others. It falls in the category of virtues. We use “trustworthy” to describe people with credibility, reliability, high integrity, benevolence, and unself-preoccupied virtues. It’s discussed in books like The Trusted Advisor as the Trust Equation.

When we see “Trust in the airline industry is down,” we should immediately ask: which meaning of trust is used here?

Do we strictly intend to indicate a decline in trust? This is trust as a noun. We can track it over time, but it should always beg the question, why? What have been the patterns of trustworthiness and propensity to trust? What is driving the state of trust lower?

If we mean that people have become less inclined to trust major airlines, this is trust as a verb. If this is the problem, is it unique to the industry? Or is it part of a general decline in propensity to trust? What kind of social intervention is appropriate? Enhanced customer service initiatives? A transparent commitment to safety? Marketing campaigns that address common pain points and offer solutions?

If we mean airlines have become less trustworthy, this is trust as an adjective. If this is the issue, what data is used to define trustworthiness? And should we seek industry-based or regulatory-based solutions to the issue? Probably both.

Objects of Trust: Personal vs. Institutional

“I don’t trust what media and news organizations say – I rely on people like me for trustworthy information.”

It may seem evident that trusting a person differs from trusting an institution. We’re not confused by, “I trust FedEx to deliver my packages, but not to babysit my daughter,” because baby-sitting requires an individual, not a firm, and we don’t think of FedEx delivery people as being in the baby-sitting business anyway. Trusting people is fundamentally different from trusting organizations.

Major trust surveys, like the Edelman Trust Barometer, say that “trust in someone like me” is trending up compared to “trust in government” or “trust in companies.” This is a category mistake.

The two types of trust are qualitatively distinct; they do not belong on the same quantitative scale. The blurring of lines is similar to that of “friends” on social media platforms, as we use the same word to describe our digital tribes that we use to describe our neighbors and old college friends. The common language must be recognized and respected, but it doesn’t have the same meanings.

Most trust is personal. If FedEx misses two deliveries in a week, my “trust” in them is seriously eroded. Yet if my best friend fails to return two calls, I am perplexed—but my trust in them is barely affected. This is not surprising. It’s not the same trust we’re discussing.

Trust in particular organizations—companies, Congress—is “thin” trust. It’s connected to branding, reliability, and reputation—but not to the more powerful personal attributes we associate with trusting individuals. Most people “distrust” Congress but are more inclined to “trust” their congressperson. This is only surprising if we think the same “trust” is at issue.

Companies that consistently score high on broad measures of trust (see, for example, Trust Across America’s Most Trustworthy Companies) are usually, on closer examination, that assiduously foster trust-based relationships between individuals—between employees and customers, among employees, with local constituent organizations.

Writers should avoid sloppy use of the object of trust—humanizing trust when we talk about institutions, for example—and readers should point this out sharply. The word “trusted” means very different things when applied to Toyota, LinkedIn affinity groups, and next-door neighbors. I may “trust” them all, but we are discussing distinct phenomena.

Actions of Trust: Trust to Do What?

“I trust my dog with my life, not my ham sandwich.”

We all understand the difference, yet we often hear sentences like, “I trust Amazon—but not Google.” The Amazon/Google difference is probably the same as the life/ham sandwich difference, but we don’t usually hear it the same way.

To see why, ask what it is that we trust Amazon and Google to do. Most likely, the utterer of that sentence means that Amazon delivers fast and reliably and that Google tracks mountains of information about us. Fast delivery and responsible guardianship of private details are very different—maybe as different as “life” and “sandwich.” And yet, we act as if we’re making a meaningful statement about corporate trustworthiness when we use the “T” word with both companies in the same sentence. We are not expressing distinct opinions about two very different phenomena.

Whenever you read (or write) something comparing levels of trust—whether between people or organizations (or across people and organizations)—always remember to ask: Trust to do what? If we had more critical readers (and writers) about the above three distinctions, the discussion of trust would be incredibly advanced.

Resources to Build Your Trust Skills:

You’ve graduated from Question Obsession 101. You’ve learned not to pepper clients with endless questions or craft that perfect “Keystone Arch Question” expecting miracles. You’re focusing on relationships, creating insights, and empowering clients.

You’ve graduated from Question Obsession 101. You’ve learned not to pepper clients with endless questions or craft that perfect “Keystone Arch Question” expecting miracles. You’re focusing on relationships, creating insights, and empowering clients.

In today’s fast-paced work environment, multitasking has become a badge of honor. We pride ourselves on juggling multiple projects, responding to emails during meetings, and switching between tasks with lightning speed.

In today’s fast-paced work environment, multitasking has become a badge of honor. We pride ourselves on juggling multiple projects, responding to emails during meetings, and switching between tasks with lightning speed. We often think of establishing trust in business relationships in sales-related roles. For instance, if I have a product or service, I will tell you how my industry knowledge and credentials will make it clear I am the person you should buy from. In short, you can trust me. I know everything there is to know about this product or service. Just ask me!

We often think of establishing trust in business relationships in sales-related roles. For instance, if I have a product or service, I will tell you how my industry knowledge and credentials will make it clear I am the person you should buy from. In short, you can trust me. I know everything there is to know about this product or service. Just ask me! Trust is complicated in many aspects of our daily lives; by comparison, trust in business seems relatively straightforward. Or is it?

Trust is complicated in many aspects of our daily lives; by comparison, trust in business seems relatively straightforward. Or is it?

MISCONCEPTION 3: CLIENTS JUST WANT YOU TO SOLVE THE PROBLEM

MISCONCEPTION 3: CLIENTS JUST WANT YOU TO SOLVE THE PROBLEM MISCONCEPTION 2: TRUST TAKES TIME TO GROW AND IS QICKLY LOST

MISCONCEPTION 2: TRUST TAKES TIME TO GROW AND IS QICKLY LOST

There are many misconceptions about trust that pervade how we think about professional relationships. While most seem harmless (think about Ronald Reagan’s admonition to trust, but verify), unless they are examined and dispelled, they will impede real trust.

There are many misconceptions about trust that pervade how we think about professional relationships. While most seem harmless (think about Ronald Reagan’s admonition to trust, but verify), unless they are examined and dispelled, they will impede real trust.