Trust and Return to Office | Part III: A Guide for Employees

In part 1 of this blog series, we refocused the return to office debate on finding common ground, founded on common goals. In part 2, we looked at what employers can do to increase trust during the transition. In today’s post, we’re examining what employees can do to build trust during the transition.

In part 1 of this blog series, we refocused the return to office debate on finding common ground, founded on common goals. In part 2, we looked at what employers can do to increase trust during the transition. In today’s post, we’re examining what employees can do to build trust during the transition.

Trust is Crucial during Return to Office

The transition back to office work represents more than just a physical return to familiar spaces—it’s an opportunity to rebuild and strengthen workplace relationships that may have evolved during remote work. While organizations play a crucial role in facilitating this transition, individual employees can take meaningful steps to foster trust with colleagues and leadership. Here’s how you can contribute to building a foundation of trust in your workplace.

Lead with Transparency

Trust begins with open communication. Maintain open and honest communication with your colleagues and superiors, and be candid about your challenges and needs during the transition. Sharing your concerns, ideas, and feedback constructively can provide crucial information about what’s working and where adjustments may be needed across the organization.

For example, if you’re struggling to adjust to in-person meetings after years of virtual collaboration, share these feelings with your team and collaborate on ways to make the transition easier for everyone. Your vulnerability can encourage others to share their own concerns, creating an environment where honest dialogue becomes the norm.

Demonstrate Adaptability

Understand that the return to the office may involve changes in routines and policies, and that your approach to work will change as a result. Demonstrating your willingness to adapt and contribute positively to the changes demonstrates emotional intelligence and reliability. When faced with new protocols or unexpected changes, approach them with a positive mindset and willingness to learn.

For instance, if your organization implements new hybrid meeting technology, take the initiative to learn it thoroughly. If office seating arrangements change to accommodate new team structures, embrace the opportunity to work alongside different colleagues. Your adaptability shows colleagues and leadership that you’re committed to making the transition work, regardless of challenges.

Remember that adaptability doesn’t mean constantly changing your approach—rather, it means finding the right balance between maintaining stability and embracing necessary changes. Share your adaptation strategies with colleagues who might be struggling, and be open to learning from others who might have found effective ways to navigate new situations.

Maintain Consistency

People trust us when they know what to expect from us. Consistency – both between your words and actions and in your behavior – builds reliability. When we are in the office, our actions are more visible than ever. Make it a priority to honor commitments, and consider setting more realistic deadlines for yourself or being more selective about which projects you take on while you are adjusting. It’s better to make fewer promises and keep them all than to overcommit and underdeliver

Be Fully Present

The office environment offers unique opportunities for meaningful face-to-face interactions. Multi-tasking during remote work was commonplace. In the office, make the most of your interactions by focusing only on the interaction you are having. Put away your phone during conversations, maintain eye contact, practice active listening, and ask thoughtful follow-up questions. Show your colleagues that you value their perspectives and ideas.

Consider setting aside time for informal catch-ups with coworkers. These conversations can help bridge the gap between professional and personal connections that may have weakened during remote work.

Respect Boundaries

Everyone will experience the return to office differently. Be mindful of personal space and respect working hours and lunch breaks. Just because someone is physically present doesn’t mean they’re always available for impromptu discussions.

Share Knowledge and Resources

Position yourself as a reliable resource for your team. Share relevant information, offer help when you notice someone struggling, be empathetic and generous with your knowledge and expertise. This collaborative approach demonstrates your commitment to the team’s success and helps build trust through mutual support.

Acknowledge and Address Conflicts

When disagreements arise, address them promptly and professionally. Avoid office gossip and instead focus on finding constructive solutions through direct communication. If you’ve made a mistake, acknowledge it, apologize sincerely, and take steps to prevent similar issues in the future.

Build Cross-Departmental Relationships

Take advantage of being back in the office to strengthen relationships across different teams and departments. This broader network can lead to better collaboration, increased understanding of organizational goals, and more opportunities for innovation.

Consider joining cross-functional projects or participating in office-wide initiatives. These experiences can help you develop a more comprehensive understanding of the organization while building trust with colleagues you might not regularly interact with.

In Conclusion …

Building trust during the return to office requires intentional effort and patience. By focusing on transparency, reliability, and meaningful connections, you can contribute to creating a workplace environment where trust flourishes.

These strategies aren’t just about making the transition smoother; they’re about laying the groundwork for stronger, more resilient workplace relationships that can withstand future changes and challenges. As you implement these approaches, you’ll likely find that the investment in building trust pays dividends in improved collaboration, job satisfaction, and career growth opportunities.

Trust is a collective effort, and when both employers and employees contribute to a culture of trust, it creates a more harmonious and productive workplace environment.

Resources to Build Your Trust Skills:

- Subscribe to our newsletter.

- Follow us on LinkedIn.

- Contact us directly to learn about private workshops.

- Explore our free eBooks.

- Join the crowd and sign up for one of our Public Virtual Workshops.

In

In

In today’s fast-paced work environment, multitasking has become a badge of honor. We pride ourselves on juggling multiple projects, responding to emails during meetings, and switching between tasks with lightning speed.

In today’s fast-paced work environment, multitasking has become a badge of honor. We pride ourselves on juggling multiple projects, responding to emails during meetings, and switching between tasks with lightning speed. We often think of establishing trust in business relationships in sales-related roles. For instance, if I have a product or service, I will tell you how my industry knowledge and credentials will make it clear I am the person you should buy from. In short, you can trust me. I know everything there is to know about this product or service. Just ask me!

We often think of establishing trust in business relationships in sales-related roles. For instance, if I have a product or service, I will tell you how my industry knowledge and credentials will make it clear I am the person you should buy from. In short, you can trust me. I know everything there is to know about this product or service. Just ask me!

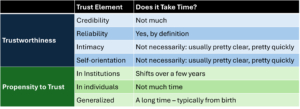

MISCONCEPTION 2: TRUST TAKES TIME TO GROW AND IS QICKLY LOST

MISCONCEPTION 2: TRUST TAKES TIME TO GROW AND IS QICKLY LOST

One of the myriad things we learned from “The Great Resignation,” where employees across the nation voluntarily resigned from their jobs, is that people are no longer willing to stay in unfulfilling roles or work for employers that do not respect their values. A powerful component of the mass exodus from organizations of all sizes and industries is the effect corporate culture has on the workplace environment, productivity, and relationships.

One of the myriad things we learned from “The Great Resignation,” where employees across the nation voluntarily resigned from their jobs, is that people are no longer willing to stay in unfulfilling roles or work for employers that do not respect their values. A powerful component of the mass exodus from organizations of all sizes and industries is the effect corporate culture has on the workplace environment, productivity, and relationships.