Trust & Leadership

Lisa McArthur, one of our esteemed consultants, tackles the topic of Trust & Leadership and provides practical, actionable steps you can take today to start improving both.

—

Into every leadership journey a little rain must fall. At some point, numbers start to head south; that key project begins to miss critical milestones. It happens to all of us. And when that rain does fall, remember that as a leader, you are defined not by your challenges – but by your response to them.

For many, missed targets or milestones trigger the instinct to micro-manage. After all, the only way to make sure you’re on top of everything is to put it all under a microscope and leave no stone unturned. Only a clear command-and-control style of leadership can help right the ship. Right?

So tempting; and yet so wrong!

The solution is not to overrule your team, it’s to get it working. Trust improves teamwork. Full stop. More reports and checkpoints will may provide more data, but chances are it is breakthrough ideas and approaches that will get you back on course. You need your team to focus on new possibilities and collectively take calculated risks.

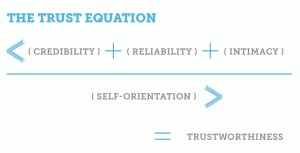

To put it simply, they need to trust each other. Sounds simple, but as a leader, what does this mean? How can you build trust within your team? The trust equation, normally a descriptor of personal attributes, has something to add to team analysis:

1. Start with Intimacy

For those not familiar with the trust equation, intimacy is about creating safety and building a safe environment. Put yourself in a team member’s shoes. They have an idea that could help bring things back on track. Should they take a risk and offer the idea up to the group? What kind of reaction will they face? In a safe environment, new ideas are welcomed and become the seeds that can germinate true breakthough thinking.

Be honest. How does your team measure up? Are new ideas welcomed and used as building blocks or are they generally dismissed? If suggestions are met with a “we’ve tried that before” or “It’ll never work”, ideas will slowly stop coming.

As a leader, how are you building a “safe” environment to ensure that your team’s ideas are heard? At your next team meeting, try starting from a place of vulnerability. Talk about the issues at hand and your role in them. By taking a risk and being vulnerable you are showing your team that it is safe for them to take risks too!

Next, ask for help. We often resist asking for help for fear of appearing weak – but paradoxically, asking for help shows vulnerability, equality and a desire for collaboration. You’ve taken a risk (again) and shown your team that it is okay to do.

The plus – most of us are hard-wired to respond to honest requests for help. Get the brainstorming started and then listen. Really listen! Ask engaging questions, clarify and let the team build on each other’s ideas. New and innovative solutions are far more likely when everyone is fully engaged and feels safe to contribute.

2. “Check your S”

The “S” in the denominator of the trust equation is self-orientation – and a high number is not good. As a leader, you have to model low self-orientation. Are you focused on what YOU need – to report on a project’s progress or the latest operational results – or are you focused on what the TEAM needs? Even those leaders with the best intentions can find this difficult.

Acting as an “I”, we start directing and stop listening. How often have you asked for the latest sales results or project update only to then provide clear and specific direction on what you think is required?

Change your focus to “we”. Instead of the “I”, ask what the team needs to be successful – and then whatever it is, do it quickly. By changing your focus to the team, your actions will show your commitment to their success. Your commitment to the team’s success, and only the team’s success, lower’s your self-orientation. Done authentically, your team will respond in kind, re-committing themselves personally to the task at hand.

3. Build positive momentum with reliability

The biggest part of Reliability is, simply stated, do what you say you are going to do. We are all familiar with Newton’s first law of motion; “An object at rest, stays at rest. An object in motion stays in motion until acted upon by an external force.” How can you, as a leader, get the ball rolling?

Start small. Have the team set small, incremental targets. It’s important that the targets are set on the team’s terms, not yours. Make sure the targets are attainable and then celebrate each success. Suddenly, you have shifted the focus from what the team can’t do to what they can accomplish. With each small win, the team builds positive momentum and once you’re moving, no one will want to be the reason things come to a halt.

At the same time, resist encouraging sandbagging, or in its more polite form, “under-promising and over-delivering.” It’s just another form of lying to your clients, and it undercuts reliability, since it literally trains your clients to expect a disconnect between what you say and what you do. Which was the whole point in the first place.

4. Be honest

As a leader, your words have power. Now is the time to focus on clear, concise messages that your team will understand and take to heart. Now is not the time for nuanced explanations.

Words matter. If you are not sure of an answer – say so (in fact, “I don’t know” is one of the most credibility-enhancing things you can say – no one will suspect you of lying about that!). You can always go get the answer, but you won’t always get another chance to prove your honesty.

In environments where things get tough or are moving quickly, even tiny errors in facts or judgments can create large ripples in the team and create that ominous “spin” that suddenly brings all activity to an abrupt halt.

Life is full of ups and downs and rainy days; leadership is no different. Strong leaders understand how to build trust and foster an environment that encourages each team member to contribute to their fullest potential. The next time your team struggles, remember – don’t take over the job yourself – instead, lead with trust!

In my last post,

In my last post,  Every age has its fads and fashions. Some of them hold up over time – competitive strategy, business process re-engineering, quality circles. Applying neuroscience to business, I suggest, will not be one of them.

Every age has its fads and fashions. Some of them hold up over time – competitive strategy, business process re-engineering, quality circles. Applying neuroscience to business, I suggest, will not be one of them. In college, I majored in philosophy. I underlined all the important parts in my texbooks – the hard, the empirical, the deductive, the categorical. I underlined about half of each book. What I skipped over were the soft and squishy parts: know thyself, be virtuous, metaphysics, that kind of thing.

In college, I majored in philosophy. I underlined all the important parts in my texbooks – the hard, the empirical, the deductive, the categorical. I underlined about half of each book. What I skipped over were the soft and squishy parts: know thyself, be virtuous, metaphysics, that kind of thing. I rarely write blogposts promoting the services we offer. But since we have something new to offer – this is one of those times.

I rarely write blogposts promoting the services we offer. But since we have something new to offer – this is one of those times. Ron Prater

Ron Prater Put Values First

Put Values First