When It Really Is “Me, Not You”

We’ve all seen the movies, or worse still, possibly heard the words – “it’s not you, it’s me.”

We’ve all seen the movies, or worse still, possibly heard the words – “it’s not you, it’s me.”

A dramatic break up scene follows. We’re left in no doubt that the ‘you’ in the scenario was a) badly dealt with, and b) probably better off in the long run given that scoundrel ‘me,’ who is typically using the line as a cheap and insincere way to get out of the relationship.

But what if it’s true?

And what does that ‘breakup’ look like in the context of a business relationship? Many of us have had challenging client situations and relationships that just felt dysfunctional. And all too often we let ourselves believe that it is the other who is the problem, not our selves. The internal dialogue becomes “It’s not me – it’s you!”

It’s the reversal of the movie plot of the relationship breakdown. We start the blame game and potentially lose sight of what really happened. (And after all, what are business relationships other than just relationships with business as the context?).

My own “it really was me” moment played out over a year of frantic project delivery for a client with tight deadlines and ambitious goals; it involved a lot of shouting, mutual frustration and ultimately a breakup. Sound familiar?

I was saved from the worst of the blame game by a very astute new analyst in my consulting firm, who unknowingly helped bring the Trust Equation even more alive for me.

Was It Me or Was It Them?

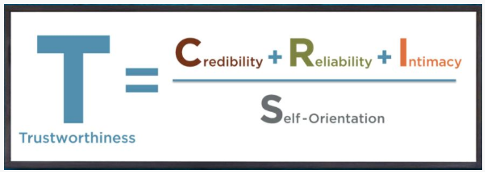

I was a big advocate of the Trusted Advisor approach, and in fact had taught the material to many people over the years. I had a story for each aspect of Credibility, Reliability, Intimacy and Self Orientation. The stories were the stuff of legends (in my own mind) and I could retell them with ease.

There was one – my go-to story – about ‘the challenging client and the breakup’ that I loved telling new hires. It had shock value and impact, and often provoked great discussion on the importance of balance in the trust equation. The story could last five minutes or 25 depending on the audience and the nuances added, but always ended, “….and that is how the client ruined our trusted relationship!”

That punchline came to an ignominious end one afternoon in a session with students in Kuala Lumpur. I had talked about how to demonstrate credibility with new ideas, reliability with delivery, and intimacy through shared experiences. After I went through my final go-to story about the client’s Self-orientation, an analyst put her hand up and asked, “You’ve talked a lot about what was in it for the client, but what did you want to get out of the relationship and project?”

A great question – and one I’d never examined. I knew I hadn’t enjoyed the project (successful though it was), and I knew the client was annoyed with me at the end (again, despite the good results) – but I’d never really examined the why. I had just thought “difficult client, next assignment please.”

Her next question went deeper. “It sounds like you just wanted to get off that project and didn’t care what happened to the client.” Ouch!

The Penny Drops – It Was Me After All

That evening I played back my own recollection of events. I realised that on at least three occasions I had thought only of my own objectives. First, I had wanted the project to be a success for me; I was looking for a promotion. Next, I had omitted inviting the client to a presentation we were making to their Board (the person was on holiday, but I could have asked them regardless). Finally, I had just wanted off the project – after all, it had been draining and challenging.

None of these instances may have been showstoppers on their own, but combined it meant my self-orientation was so poor that the client would had to have been made of stone not to distrust me. All those great results, all that thought leadership and intimacy had been slowly eroded by me wanting to achieve my goals – not theirs. The relationship had begun to break down – and all at the same time my inner voice was telling me, “It’s them not you!”

What a wake-up call for me, three years of believing they were the problem!

The next time I delivered the Trusted Advisor session the story hadn’t changed – but the punchline had. Instead of the casting the client as villain and me as the poor beaten up consultant, my conclusion was, “And this is how my self-orientation ruined a perfectly good trusted relationship.”

From time to time I still see that client in airports. We both acknowledge that it was a tough assignment, but we both know now that “It wasn’t you, it was me!” isn’t just a line in the movies. It’s real. And unlike in the movies, sometimes it’s really true.

I’ve often wondered: is our real workplace office the coffee shop?

I’ve often wondered: is our real workplace office the coffee shop?

Credibility is one piece of the bedrock of trust. If people doubt what you say, all else is called into doubt, including competence and good intentions. If others don’t believe what you tell them, they won’t take your advice, they won’t buy from you, they won’t speak well of you, they won’t refer you on to others, and they will generally make it harder for you to deal with them.

Credibility is one piece of the bedrock of trust. If people doubt what you say, all else is called into doubt, including competence and good intentions. If others don’t believe what you tell them, they won’t take your advice, they won’t buy from you, they won’t speak well of you, they won’t refer you on to others, and they will generally make it harder for you to deal with them. Are you an ENTJ? An ISFP? An Aries or a Pisces? You may know your Myers Briggs Type Indicator, and you no doubt know your birthday–but what about your Trust Temperament™? How do you go about building a trustworthy relationship with another person?

Are you an ENTJ? An ISFP? An Aries or a Pisces? You may know your Myers Briggs Type Indicator, and you no doubt know your birthday–but what about your Trust Temperament™? How do you go about building a trustworthy relationship with another person?