The Dark Art of Ghosting in Business

I first became aware of “ghosting” as a concept over a decade ago, when a young friend informed me she had been “Caspered” by a boyfriend. I had to ask her to explain.

I first became aware of “ghosting” as a concept over a decade ago, when a young friend informed me she had been “Caspered” by a boyfriend. I had to ask her to explain.

In case you’re as clueless today as I was at the time, here’s the Urban Dictionary’s definition. Key line:

- The act of suddenly ceasing all communication with someone the subject is dating, but no longer wishes to date. This is done in hopes that the ghostee will just “get the hint” and leave the subject alone, as opposed to the subject simply telling them he/she is no longer interested

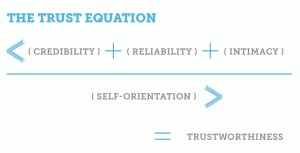

Interestingly, even as woke a place as the Urban Dictionary includes a near-moral judgment about the phenomenon: it is “closely related to the subject’s maturity…[and] proves the subject is thinking more of themselves than the ghostee.” A rather obvious nod to the concept of Self-Orientation, the denominator in the Trust Equation.

Never mind the ethical angle; I don’t want to come off as just some moralizer (not that there’s anything wrong with that). I want to state the case for what a stupid, short-term, self-harming phenomenon it is.

Business Ghosts

First of all, ghosting has evolved beyond the dating world. Some business examples might include:

- Firms ghosting interview candidates somewhere past the beginning of the recruiting process

- (Interview candidates ghosting the recruiting firm in the same situation)

- Contractors ghosting vendors who’ve responded to an RFP process (and vice versa)

Basically, any business situation in which an (even mildly) uncomfortable situation is dealt with by simply opting out of normal civil conversation.

Some more perspective:

- A 2019 Robert Half study shows that 28% of respondents had backed out of a job after accepting an offer.

- A 2019 Staffing Industry Analysts survey showed that over 40% of respondents say ghosting a potential employer is acceptable. 35% say it’s “very unreasonable” for a company to ghost a potential employee, but only 21% think it’s “very unreasonable” for the potential employee to ghost the potential employer.

- A friend with a small IT consulting firm who depends on subcontractors told me of recently being ghosted by a sub after having gotten verbal confirmation of commitment to work on a time-critical job.

There is a line of argument that says millennials and Gen Z are to blame. Weaned on social media and anchored to their cellphone screens, the argument goes, we are raising a generation of socially incompetents. (For an excellent take on the issues facing this age cohort, I recommend Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s most recent book, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure).

However, I’m not going to go there regarding ghosting, because I don’t want to let the rest of us off the hook. As the Urban Dictionary notes, it’s an issue of maturity: and just because it’s an age thing doesn’t mean it’s a generational thing. It’s something that hopefully we grow out of as we get older.

So, let’s look at it from the point of view of the ghoster, and the ghostee.

When It’s OK to Ghost

This one’s easy.

Basically, never.

Sure, you can come up with some convoluted morally-ambiguous scenarios in which non-involvement or silence is somehow the lesser of two evils. But let’s get real: it’s simply not OK to ghost people in the midst of normal commercial-human behavior.

Beyond the dictates of normal social behavior, there are plenty of good reasons. Your reputation will suffer, as will that of your firm. You will create unnecessary resentments. You will annoy at best and hurt at worst other people. You burn bridges. You set a bad example. You create bad habits.

Really, that should be enough. Just Don’t Do That.

What to Do When You’re Ghosted

Basically, you’ve got four choices; and only one of them is acceptable.

- Keep hounding them. Classic can-kicking down the road. Postponement is not solution.

- Reach out positively to give them another chance. Definitely worth one try. Not worth two, because it’s likely to just drive the offender deeper into their behavior. Plus, life is short.

- Publicly shame them. Tempting, but to all the wrong parts of your psyche. Resentment is like taking poising and waiting for the other person to die. Don’t indulge in it.

- Resolve never to do business with them again, and move on. They’ve shown you their true colors; time to believe them, and move on.

So, what can you do if you’re ghosted? Honestly – nothing. Find some learning in it, and move on.

How to Prevent Being Ghosted In the Future

This may be the only situation worth talking about.

You can do a few things reduce the chances of it happening again.

- For one, maximize emotional bandwidth at the outset. If you can’t meet personally, then do video calls rather than audio. If you can’t do video calls, then do audio calls rather than email. If you can’t do phone calls, then write lengthy emails rather than short ones. The more personal connection you establish up front, the less people are likely to ghost you.

- For another, take a small risk on them at the outset. The logic here is that people tend to reciprocate. If you trust them, they’re more likely to be trustworthy with you. That might mean a small upfront payment; or a sharing of some intellectual property; or a sharing of information about your own business. Your choice: the point is to take a risk, so they’ll take a risk on you.

- Share something about yourself that is personal early on. Again, people tend to reciprocate, and they’re likely to respond similarly. People are more likely to come to you with conflicts if you’ve had some level of interpersonal sharing than if they think they “really don’t know you anyway, so what the heck.”

You’ll notice these are all small ways of increasing trust up front. Establishing trust up front is the best inoculation against the violation of trust later by someone who’s vulnerable to the immature and destructive act of ghosting.

And, not that it’s your job, but doing so will help add to the emotional maturity of the contractor, and make things a little better in the world at large. Not a bad deal: reduce your risk, and help fix a tiny part of the world at the same time. Be an ambassador of trust.