Two Paths to a Trusted Business

Let’s try a thought experiment. Imagine that you’ve been put in charge of an effort to improve the level of trust that people have in your organization (which could be a company, an institution, a business unit, whatever).

Let’s try a thought experiment. Imagine that you’ve been put in charge of an effort to improve the level of trust that people have in your organization (which could be a company, an institution, a business unit, whatever).

You have two choices, I would suggest. One I’ll call “outside-in,” and the other “inside-out.” Both have a role, but one should get more emphasis.

The outside-in approach might involve hiring a PR or consulting firm to help you, and focuses on such issues as messaging, metrics, process and procedures design, publicity, incentives, market research, designated trust officers, behaviors, KPIs and the like.

The inside-out approach involves improving the personal trustworthiness and the propensity to trust for all employees of your organization. It also involves messaging (though mainly internal), but as well such methods as leading-by-example, education, role-modeling, performance reviews, and mentoring.

Which works more quickly? Probably the outside-in approach. Which lasts longer? Probably the inside-out approach. Which provides the biggest impact? Again, probably the inside-out approach.

What’s Going On Here?

What’s going on here is the interplay between institutional trust and interpersonal trust. It raises questions like, “Which comes first?” “Can you have one without the other?” And, “How do they interact?”

If your objective is to improve the perceived trustworthiness of your organization (the thought experiment I proposed above), then do you best get there by working at the institutional level (“outside-in”) or at the interpersonal level (“inside-out”)?

I’m not trying to set up a forced dichotomy. In most cases you should use a little of both approaches. This is not an “either/or” situation, it’s “both/and.”

BUT: my decidedly unscientific research suggests that the typical business response is to lean far more heavily on the “outside-in” approach, and to downplay the “inside out” approach. This is unfortunate.

It’s unfortunate because people – customers, clients, employees, the public at large – trust institutions only narrowly, whereas they trust people more deeply. If I ‘trust’ FedEx, it doesn’t mean I trust the FedEx driver to babysit my grandchild; but if I do trust that driver, I will probably trust FedEx too.

I trust an institution to behave consistently in certain ways, to have certain policies in place, to provide relevant expertise and capabilities. I trust people to do the same things – but I also want more from them. I want people to be flexible, good listeners, to be curious and empathetic and to care about my experience. These are traits that only people can have. If the people I deal with have these interpersonal traits of trust, I am more likely to generalize and assume good things about the organization they are part of.

If I’m right about that, then why do organizations default so heavily to the “outside-in” approach to institutional trust? I think it’s because the toolset of business these days is overwhelmingly analytical, data-driven, and behaviorally biased. We are taught to “trust but verify,” and that “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” An entire online generation is being taught to eschew “common sense” and “gut feel,” yet to pursue automated imitations of those very human instincts.

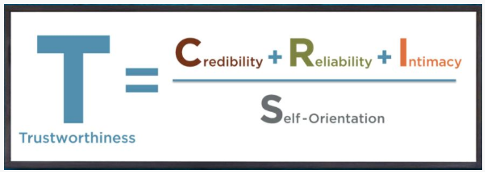

Improving reliability and expertise is easy; you can come up with dozens of metrics and qualifications. These can be measured and trained for. Not so when it comes to empathy, curiosity and paying attention. They are implemented by “messier” human processes like imitation, Socratic questioning and stories. And yet, the presence of those abilities not only creates trust with an individual but reflects on the institution as well.

Suppose you are the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, facing concerns about ethical violations. Do you a) promulgate legal guidelines (and get critiqued for lack of enforcement rules), or b) gain consensus among the individual Justices that “going forward, we’re just not going to behave in ways that even hint at raising ethical questions, and if you have a doubt about an issue, surface it with the group?”

Suppose you are in charge of customer acquisition for a SaaS consulting firm. Do you develop an outreach program that a) solely and self-centeredly promotes the track record and capabilities of your firm, or b) recognizes and emphasizes something unique and interesting about the potential customer as a key part of reaching out to them?

Suppose you are head of LinkedIn’s efforts to increase networking and linkages between members. Do you create a program that a) automates a linking process with a self-seeking message header like “I’d like to connect,” or b) encourages members to seek out and comment on the members’ relevant shared spheres of interest?

And here’s one about which you don’t need to make suppositions – Wells Fargo, which endured a self-inflicted scandal in 2016. It brought down one CEO, and then another three years later, and the bank incurred billions in fines. Wells Fargo ran two big marketing campaigns admitting wrongdoings and focusing on how the bank was rebuilding trust.

Sounds good, but how did that play out? As the new vice chairman of public affairs said in 2023, “you can’t tell a story that isn’t true…if you’re going to say what you’ve done, or what you plan to do, you better be doing it.” In his telling, this classic outside-in approach was false, and still failing. In early 2023, the bank paid $1 billion to settle a shareholder lawsuit that accused the firm of overstating its level of compliance with orders stemming from the 7-years-prior scandal.

Perhaps you’ve heard the saying that “problems aren’t solved at the levels at which they’re created.” It applies here. If you’d like your organization to be more trusted, don’t rely just on institutional tools. Instead, remember organizations are made up of people, and they interact with people. Operate at that level as well.

Personal trust doesn’t exist solely outside of institutional trust. Among other things, it is a necessary condition for achieving institutional trust.

Trust-Based Resources to Maximize Your Team’s Potential:

- Build trust on your terms through our Self-Paced Online Courses.

- Join the crowd and sign up for one of our Public Virtual Workshops.

- Subscribe to our newsletter.

- Follow us on LinkedIn or Instagram.

- Contact us directly to encourage cultural change in your organization through a trust-centric framework that pulls everyone together.

Fourteen years ago I wrote the following thoughts on New Years resolutions. It feels even more relevant this year, as we breathe a collective sigh of relief that 2020 is finally over.

Fourteen years ago I wrote the following thoughts on New Years resolutions. It feels even more relevant this year, as we breathe a collective sigh of relief that 2020 is finally over.

emotions, feelings, reactions, perceptions, elephants-in-the-room, the unspoken issues. All these can be raised in the context of the-personal-in-business: things that are happening in the workplace.

emotions, feelings, reactions, perceptions, elephants-in-the-room, the unspoken issues. All these can be raised in the context of the-personal-in-business: things that are happening in the workplace. It’s fair to say the vast majority of us have not experienced a global public health crisis at a scale similar to the one we are experiencing right now with COVID-19.

It’s fair to say the vast majority of us have not experienced a global public health crisis at a scale similar to the one we are experiencing right now with COVID-19. I’ve often wondered: is our real workplace office the coffee shop?

I’ve often wondered: is our real workplace office the coffee shop?

Twelve years have passed since I first wrote the following thoughts on New Years resolutions. Frankly, it was good. And frankly I haven’t been able to write a better one.

Twelve years have passed since I first wrote the following thoughts on New Years resolutions. Frankly, it was good. And frankly I haven’t been able to write a better one.