In a word – no.

But the reason why is not the usual critique. Let me explain.

Origins in Distrust

Bitcoin was born of distrust. Its original fan-base was an amalgam of nerds, futurists, libertarians and survivalists. They were enticed by several features of the new crypto-currency:

- a decentralized network, beyond the control of governments and regulators

- a secure payment system, guaranteed by blockchain technology

- a fixed supply (fixed by innate technological design), preventing inflation by printing press.

All of these features were and are attractive to those who distrust central authority (on some level, all of us). But while the first two features are indeed truly intriguing, the third one turns out to be a poison pill in sheep’s clothing.

Success of Bitcoin

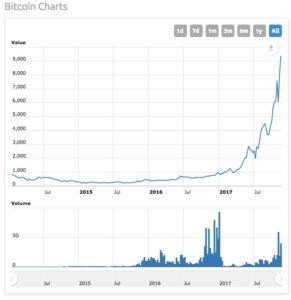

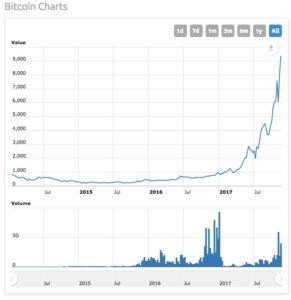

Bitcoin has been a wild success story by most metrics, certainly including its exchange rate, which has been meteoric (see graphic). Many analysts and investors are dazzled by its success, most recently including the famed Motley Fool investor newsletter, which has just jumped on the Bitcoin Bandwagon. A few cynics, most famously Jamie Dimon, have called it a ‘fraud’ or a bubble.

But no one that I’m aware of has pointed out a fundamental contradiction at the heart of Bitcoin – one which ultimately makes the doomsayers right.

(Note: I’m not at all criticizing the underlying power of blockchain, of which Bitcoin is merely one instantiation; blockchain has immeasurably great opportunities to transform the world in powerful and positive ways).

The Role of Bitcoin

The most basic argument for Bitcoin is that it will revolutionize the world of currencies, for the reasons stated above: decentralized, secure – and that third item, a fixed supply of Bitcoin. Never mind the side arguments about gold and international currencies – its stated value is its power as a currency.

At some point in the future, the argument goes, Bitcoin will become accepted massively as a medium of exchange. Note: the value of Bitcoin does not rest on a nation’s economy, or a valued good (like gold); it rests on its future value as a preferred medium of currency. Period.

But what if its value as a currency is, literally, unachievable?

Read on.

The Underlying Value of Bitcoin

The proponents of Bitcoin – this Nasdaq article is a good example – will tell you that Bitcoin has value because of “the network effect.” The more people use it, the more valuable it will become. The massive volatility that exists in Bitcoin right now will settle down and stabilize as it becomes an accepted means of currency exchange around the world.

Sounds plausible, right? We’ve seen the network effect in technologies as simple as the telephone and as complex as Facebook.

But there is one massive problem, which everyone I’ve seen who writes about it tends to skate right by.

Is Bitcoin a Currency, or an Asset Class?

Most fans will tell you it’s both – and they don’t see a contradiction between the two. But there IS a contradiction, because of one of the core features of Bitcoin – its limited-by-intent supply of Bitcoins (currently 16 million, and capped by design at a maximum of 21 million).

What you want from a currency is a stable level of purchasing power. What you want from an asset class is an appreciating price.

- An asset that has high volatility and a growth rate of 500% is called a great investment opportunity;

- A currency that has high volatility and an exchange rate variation of 500% is called hyper-deflation.

The fact that Bitcoin is limited – by design – to 21 million bitcoin means that, by the immutable laws of supply and demand, the more popular it becomes, the higher the price is going to be. Until it is less popular, when it will drop like a rock.

In other words, the limited supply aspect of Bitcoin guarantees that it will behave as an asset class – and not as a currency. Note this is not seen as a bug – this is pitched as a feature.

A currency that is by nature volatile is a currency that will attract only speculators – and the more volatile, the more that is true. After all – if you expect Bitcoin value to rise, why would you ever use it to buy a car, or to settle debts? You would only be incentivized to hold on to it.

And if you expect Bitcoin value to drop, why would you ever want to hold on to it? You would only be incentivized to short-sell it – or to unload it on a bigger fool. (And as any trader can tell you, the latter is better: the market can stay crazy longer than you can stay liquid).

The only exceptions are, as Jamie Dimon pointed out, international thieves for whom short-term volatility costs are outweighed by the chance to conduct illicit business and not get caught.

Bitcoin is Not a Ponzi Scheme: It’s Worse

The term “Ponzi scheme” gets overused. Technically it’s a situation where the later investors buy out the early investors at inflated valuations. This is not exactly the problem with Bitcoin.

Bitcoin is more akin to the original tulip craze. But even there, everyone saw tulips as an asset class, and the smart money either stayed out or schemed to unload an over-valued asset to the greater fool.

This is worse than tulips. Here the scam is based on a fundamental confusion between assets and currencies. To put it simply, it’s closer to being a little bit pregnant:

You simply cannot be both a currency and an asset class.

Muddled-thinking Bitcoin fans are fond of citing gold as a counter-example. It’s not. Unlike Bitcoin, the supply of gold is not fixed; it varies with price, as known deposits become more or less economically viable. (The term “Bitcoin mining” has had the unfortunate effect of metaphorically linking Bitcoin to precious metals). Gold even has some serious industrial uses; about 10% of it is used in industry of various types. Bitcoin, by contrast, has no stated utility other than as a currency.

To those who say there are traders in all currencies, and there are ebbs and flows of price, yes – but nowhere near this order of magnitude. Currency traders swoon over volatility of a few hundred basis points. And if things were to get really out of hand with your dollar or your renminbi, you can always print more of them to stabilize the price. Not so if your currency supply is fixed, forever, by design.

The Trust Scam: Bitcoin as Snake Oil

Nearly all the talk about Bitcoin lately has been about its stellar performance as an asset class, precisely because that’s how it’s being treated. And, as I’ve argued, it always will be.

The ultimate vision of Bitcoin – the argument that Bitcoin will reach its true value as a currency – is little more than snake oil. It can never function as a currency as long as the supply is statutorily limited, because it will always be subject to the whims of supply and demand; which in turn makes it unsuitable for the most basic function of a currency, which is to serve as a vehicle of exchange. Bitcoin is a trader’s delight – a digital volatility machine – and therefore a currency user’s nightmare.

In the end, Investopedia has it right: Bitcoin only has value “because it is popular.” It may not have a central bank behind it, which some see as a plus, but it also has no economy behind it. Because of its internal poison-pill design, it is doomed to forever be treated like an asset class, based ultimately on how many people have bought into the fiction that a limited-supply currency can ever be anything other than a vehicle for speculation of the greater-fool variety.

It’s ironic that a high level of distrust in national currencies gave rise to the enthusiasm for something so massively more untrustworthy.

You can trust investment bankers to cut to the chase. It’s their job, and they’re very good at it.

You can trust investment bankers to cut to the chase. It’s their job, and they’re very good at it.

Michael Lewis’s new book

Michael Lewis’s new book