Putting the “I” into “Intimacy”

“Intimacy” belongs in business. Yes, intimacy. Not the kind that was the subject of classic ‘40s movies, but the kind that is essential to building trust.

“Intimacy” belongs in business. Yes, intimacy. Not the kind that was the subject of classic ‘40s movies, but the kind that is essential to building trust.

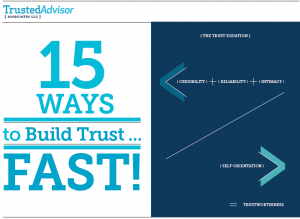

The Trust Equation

The Trust Equation is familiar to many of you, both regular and even occasional readers of this blog. It’s a formula for measuring our own trustworthiness through the Trust Quotient assessment.

For many people, Intimacy is the hardest piece of this simple formula to grasp and to put into practice.

Deconstructing Intimacy

We look at Intimacy in business relationships as having three components:

- Discretion – the wisdom to know what to do with information another shares with us

- Empathy – the ability to see another person’s point of view from the inside out; to identify with another person’s feelings, and

- Risk-taking – vulnerability

The first two are about the other person: safeguarding their sharing, picking up on their feelings and acting appropriately.

The last one – risk taking – is about you.

The “I” Part

The “I” part of intimacy means opening yourself up to the other person. It means becoming vulnerable. It really is all about you, and the risks you’re willing to take.

We often get asked what Intimacy sounds like or looks like in business settings. I would argue that it doesn’t require knowing the name of your client’s or colleague’s kiddos or pets (though for some people that works as Intimacy too), but rather saying or doing the thing that feels risky.

It may be as simple as asking for feedback, when you really don’t want to hear bad news: “I don’t feel that I’m doing this job to your satisfaction. Can we discuss it?”

It may be revealing something personal about yourself, perhaps saying at the start of a big presentation: “Although I am completely convinced that our plan is a good one, I find myself a little intimidated talking to this senior group.”

It may be a matter of just voicing something you both know to be true: “I believe your boss didn’t think we were the right supplier for this job, and you went out on a limb to get us approved. What are your particular concerns? How can we make you look good?”

The I in Risk, and in Trust

A good rule to remember about trust in business is that it’s generally not about you. Except, of course, when it is. And when it comes to intimacy, it is about you.

In our White Paper we show with hard data that the “I” factor drives more trust than the other three. And it is where risk shows up: taking the risk of Intimacy is what creates the reciprocal exchange that is trust.

If you’re lucky, your client or colleague or boss will lead by taking the first risk. If you don’t trust to luck, make some luck of your own. Take a risk. Lead with intimacy. Create some trust.

You can do that.

We’re pleased to announce the release of our latest ebook:

We’re pleased to announce the release of our latest ebook:  Are you an ENTJ? An ISFP? An Aries or a Pisces? You may know your Myers Briggs Type Indicator, and you no doubt know your birthday–but what about your Trust Temperament™? How do you go about building a trustworthy relationship with another person?

Are you an ENTJ? An ISFP? An Aries or a Pisces? You may know your Myers Briggs Type Indicator, and you no doubt know your birthday–but what about your Trust Temperament™? How do you go about building a trustworthy relationship with another person? I was in Toronto. Barely glancing at a $10 bill, I thought, “Ha—they misspelled the word ‘dollar,’ those silly Canadians.”

I was in Toronto. Barely glancing at a $10 bill, I thought, “Ha—they misspelled the word ‘dollar,’ those silly Canadians.” In case you missed it, here’s your opportunity to get a copy of our latest eBook, “

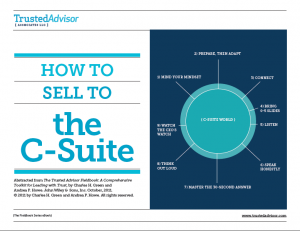

In case you missed it, here’s your opportunity to get a copy of our latest eBook, “ We’re about halfway through our countdown of Trust Tips leading up to the release of “The Trusted Advisor Fieldbook: A Comprehensive Toolkit for Leading with Trust,”

We’re about halfway through our countdown of Trust Tips leading up to the release of “The Trusted Advisor Fieldbook: A Comprehensive Toolkit for Leading with Trust,”  We all know the power of stories in business. We know too that it’s the heroes who give stories power. The hero may be a person, a brand, a company, or it may be the listener. When the story and the hero are strong, it resonates with the audience.

We all know the power of stories in business. We know too that it’s the heroes who give stories power. The hero may be a person, a brand, a company, or it may be the listener. When the story and the hero are strong, it resonates with the audience. The title says it all: to help teams perform better, add more women. An intriguing research project highlighted in the June 2011 issue of the Harvard Business Review by

The title says it all: to help teams perform better, add more women. An intriguing research project highlighted in the June 2011 issue of the Harvard Business Review by  Supposed you asked me the score of the latest Boston Red Sox vs. New York Yankees game, and I told you “12.”

Supposed you asked me the score of the latest Boston Red Sox vs. New York Yankees game, and I told you “12.” During a recent conversation, a friend–General Counsel for a large listed company–mentioned that she does not feel appreciated by her CEO for all the work she does; and that feels disheartening.

During a recent conversation, a friend–General Counsel for a large listed company–mentioned that she does not feel appreciated by her CEO for all the work she does; and that feels disheartening.