Sex, Lies and Memory. And Trust.

She says he sexually assaulted her. He categorically denies it.

Surely one of them must be lying, and a Senate hearing is the right place to get to the bottom of it.

NOT.

I don’t usually write about current events, but sometimes a teachable moment arises that just begs to be waded into. So here we go.

Memory

Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History podcast has two episodes (three and four, season 3) devoted to the issue of memory. His starting point is the memory that both he and a NYC neighbor have about their interactions on the morning of 9/11.

Both are utterly confident about their detailed recall: and yet each is at complete odds with the other. Clearly they cannot both be right. Clearly one must be lying – right? Yet each vehemently denies it.

Now let’s imagine two people trying to recall traumatic events of 30 years ago, when both were in their teens. One may have been very drunk, and may have behaved very badly toward the other. Or maybe not.

- Is it possible that the accused acted so far out of character in his drunkenness that his unconscious blotted out the memory? (Not to mention plain old drunken blackout effects).

- Is it possible that the accuser felt so traumatized by some event that her unconscious, talking to no one else over the years, scrambled dates, names, and even events?

- What are the odds that either party has crystal-clear memories of what transpired at a teen-age party three decades ago? Is it possible that each might have subtly and unconsciously rewritten history just a tad?

Not only is it possible, it’s downright likely. Human memory is far from the tabula rasa we like to believe. The boundaries and limitations of eyewitnesses and their memory have been well discussed in the law.

A Tale of Plagiarism

I faced this myself. Years ago, in the midst presenting some material to a faculty at a well-respected US University, I was publicly and dramatically accused of plagiarism.

I was astonished, outraged, and indignant. I had done no such thing! The audience was entirely on my side, embarrassed on my behalf for the rudeness of the accuser.

Yet in the following four hours, doubt began to seep in. I slowly peeked back into the past, and realized that in fact I had taken some material, used it, and somewhere along the line forgotten to include the original citation. My accuser was right – to my horror!

By the end of the day, I publicly apologized to my hosts, and to the accuser.

I felt bewildered: what was happening to my memory, my ethics – my sanity.

But I have since learned that Malcolm Gladwell was right. Memories are very tricky things.

It is not at all impossible to believe that both Kavanaugh and Ford are utterly sincere. It is extremely unlikely, in my opinion, that one of them is “lying,” in the sense that we usually mean.

And yet, we are about to play out in public what is billed as a morality tale – but what is really a humanity tale.

The Court of Binary Opinion

A public senate hearing is about the worst place to find “the truth” about what happened. It is high stakes; it is being proposed in very little time; the pressure is enormous; it is as public as can be; there has been almost no investigatory work done. And yet it appears we’re about to pit one fallible human’s memory against another – ostensibly in the search for “truth.” What a débâcle.

Why is such a polarizing event about to take place? In one way, it fits with the increasing narrative of us-vs-them politics of division that is overwhelming us.

In Jonathan Haidt’s new and excellent book, The Coddling of the American Mind, he and co-author Greg Lukianoff identify three Great Untruths. One of them is “We are Right, and They are Wrong.”

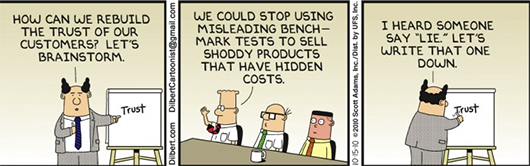

Polarization, tribalism, victimhood and blamethrowing are all the death of a reasoned democracy. This event – billed by each side as The Truth vs. The Liar – can serve no good purpose, but will be one more false binary division of good people.

What can you do? Don’t get sucked in. Recognize that memory is fickle, that people are not all good or all evil, that “the truth” is rarely black and white. Most of all, don’t view the political theater about to be served up as a morality play, but rather as a sad example of our failure to see people as human, and to deal with them in human-respecting ways.