The Problem with Lying

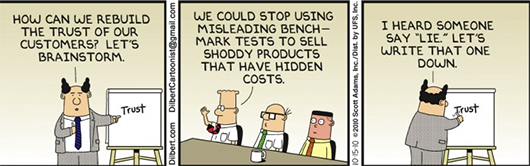

Dilbert on trust and lying:

Scott Adams nails it. With a sledgehammer, as usual. The pointy-haired boss is ethically clueless, and blatantly so.

We all get the joke, much the way we get the old George Burns line, “the most important thing in life is sincerity – if you can fake that, you’ve got it made.”

But sometimes it’s worth deconstructing the obvious to see just what makes it tick. So at the risk of stepping on the laugh line, let’s have a go at it.

Lying and Credibility

The most obvious problem with lying is that it makes you wrong. Anyone who knows the truth then immediately knows, at a bare minimum, that you said something that is not the truth, aka wrong.

The shock to credibility extends even to denials. Think Nixon’s “I am not a crook,” or Clinton’s “I did not have sex…” or the granddaddy of them all, the apocryphal Lyndon Johnson story about getting an opponent to deny having had sexual relations with a pig. In each case, the denial forces us to consider the possibility of an alternate truth – and the damage is done.

But credibility is the least of it. There are two other corrosive aspects of lying: evasiveness, and motives.

Lying and Evasiveness

When you think someone is lying to you, you likely think, “Why is he saying that?” Evasive lying is rarely as direct as the Dilbert case; more often it shows up in white lies, lies of omission, or lies of deflection. “You know, you can’t really trust those damage reports anyway,” “I wouldn’t be too concerned about the service guarantee if I were you,” and so forth.

If the first response to a lie is to doubt that what is stated is the truth, then the second response is to wonder what the truth really is. And we sense evasiveness as we run down the list of alternate truths, each more negative than the last.

Lying and Motive

But the most damning aspect of lying is probably the doubt it casts on the liar’s motives. We move from “that’s not true!” to “I wonder what really is true,” to “why would he be saying such a thing?”

To doubt someone’s motives is to add an infinite loop to our concerns about the lie. First of all, motive goes beyond the lie, to the person telling the lie – who is now incontrovertibly a liar.

Second, the rarest of all motives for lying is an attempt to do a greater good for another. Despite frequent claims that “I did it for (the kids / the parents / justice), almost all motives for lying turn out to be self-serving at root. (Including the lies we tell ourselves about why we’re telling lies). Why would he do such a thing? Because there was something in it for him, that’s why! It’s almost always true.

And if people act toward us from selfish motives, then we know we have been treated as objects – as means to an end and not as ends in ourselves. This is unethical in the Kantian sense.

Worst of all, bad motives call everything else into question. “If he lied about this, then how can I know he was telling the truth about that? Or about anything else?” This is why perjury is a crime, and why casting doubt on someone’s character is a common way to counter their statements.

Recovering from Lies

We’ve all told lies. At least, everyone I know has. Okay, I have. We can often be forgiven, just as we can forgive others their lies to us. To forgive and to be forgiven, the liar must express recognition and contrition around the full extent of the lie, and then some.

This can be done more easily for the wounds of credibility and evasiveness. “I was wrong to do that, I know it, and I am sorry.” It is harder to forgive the part about motive, because it goes to something much deeper. How can someone be believed about changing their motives? How easily can you change your own?

Charlie, This is no doubt one of your most important posts. It strikes to the heart of all human relationships and as you noted, none of us can look in the mirror without some degree of guilt when it comes to absolute honesty. But this is a blog aimed at a business audience. JFK and FDR were great leaders, yet they certainly failed the test in their personal relationships. Many of our business leaders today have failed that test on both personal and business levls. I had a colleague who wouldn’t work with another colleague who had at one point had an affair, as he said “if he cheated on his wife, how can I trust him”. We are all imperfect. But there are important questions we can ask every day: Am I being honest about our capabilities? Am I considering the client/customer’s interests? Will my product perform as promised? I don’t have to be a perfect person to get those questions right…and there isn’t any reason that I shouldn’t. Rich

Thanks Rich, and great points about how to integrate integrity with human fallibility.

As Rich said, an important post, Charlie.

For me, the greatest utility is to lay bare the flaw in the strategy of white lies and omissions. They generally don’t work–and if they do for a little while, when the problem is uncovered, the damage is multiplied.

Gives more courage to tell the uncomfortable truth, as you’ve been advocating so eloquently as long as I’ve known you.

Thanks.

Thanks Mark,

Always good to have company on the not entirely popular view that white lies are usually poisonous.

Didn’t go something like this…

Marge, “I can’t believe it Homer, you lied to me”

Homer, “It’s not just me Marge. It take two to lie, one to lie and one to listen.”

As good an excuse as I’ve ever heard. So it’s my fault as well?!