Operating Transparently

Transparency is one of the Four Trust Principles for creating trust-based organizations. The other three are other-focus, collaboration, and a medium-to-long term perspective (aka relationships over transactions). Here’s the business case for transparency.

The article Is Transparency Always the Best Policy? first appeared a few years ago in Harvardbusiness.org. The article is about Paul Levy, President and CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and the answer to the blog’s question, based on this sample of one, would appear to be a resounding ‘yes.’

In matters great and small, Levy has simply made it an operating practice to behave transparently. His great results may surprise many, but they make a great deal of common sense.

If you are transparent about your activities, you are saying you have nothing to hide. If you have nothing to hide, then people trust what you do.

If you are transparent about what you say, then you don’t risk saying one thing to one person and another to another. You don’t appear to be two-faced; you appear to have integrity—you say the same thing to all persons. (And, it’s a lot easier to remember what you said if there’s only one version).

If you are transparent about what you think, then people can observe your thinking, and see that you are not editing what you say. They feel you are available to them, that you are not segmenting them off.

If you are not transparent in your actions, your words, and your thoughts, then people wonder about your motives. Why are you doing what you’re doing?

What is it you really mean when you say something? And what are you really thinking when you’re thinking?

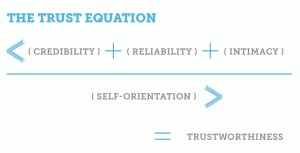

Suspicion about motives colors every aspect of trust—it affects your credibility, your perceived reliability, and the degree to which people confide in you. The antidote to a bad case of suspicion is transparency. It’s as true in the financial and regulatory world, in the world of negotiation, and in the world of accounting, as it is interpersonally.

So Why Aren’t We All Transparent?

With all the obvious advantages that transparency conveys—why aren’t we all more transparent more often?

There are a thousand answers, varying in particular, but with some common threads in general. At the root of it, I think, is fear.

Fear that others will take advantage of us. Fear that we will be misunderstood, or shamed. Fear that others will see the true inner “me” and thus steal the faux power we foolishly think we maintain by being opaque.

Transparency is both a result of lowered fear, and a cause of lowering fear. Sharing information with another encourages another to share with us. Disclosing information within a company—as Paul Levy did so frequently—begets teamwork and lowers suspicion.

The willingness to be transparent in negotiation helps the other party figure out what it is that you want—so the paradoxical result of taking a risk is that you increase the odds of getting what you want.

Transparency is an invitation to collaboration and connection. It lowers fear, it increases trust.

It feels like taking a risk, but it’s really risk-mitigation in disguise.

Operating transparently isn’t just a hospital procedure.

Nowhere am I so desperately needed as among a shipload of illogical humans.

Nowhere am I so desperately needed as among a shipload of illogical humans.