Disclosure Is Not Transparency

Transparency, most of us would agree, is a positive thing. And disclosure is an obvious way to get there.

But transparency and disclosure are not the same thing. And confusing them can actually harm transparency.

So – what’s the difference between disclosure and transparency?

Transparency and Trust

Besides “able to transmit light,” the dictionary defines transparent as:

- easily seen through, recognized, or detected: transparent excuses.

- manifest; obvious: a story with a transparent plot.

In the simplest business terms, “transparent” means you can tell what’s going on.

If the link between transparency and trust isn’t self-evident, here are a few citations to help clarify it:

- Former PwC Chairman Sam DiPiazza and Harvard Business School professor Robert Eccles wrote in Building Trust: The Future of Corporate Reporting about the critical role of transparency as a necessary, albeit not sufficient, key to greater trust in business at large;

- US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously wrote, “Sunlight is the best disinfectant;”

- In Bob Hurley’s book The Decision to Trust, he makes transparency critical to one of his ten factors affecting trust;

- In my own work, transparency is one of the Four Principles of Trust.

If I can see what’s going on, I know that I am not being misled. Motives become clear. Credibility is affirmed. Transparency is indeed a trust virtue.

Disclosure

Disclosure is a time-honored tool of regulators to achieve transparency. Food and pharmaceutical manufacturers are required to disclose ingredients, medical authors are required to reveal payment sources, the SEC frequently proposes disclosure as a tool, and so on.

Certainly you can’t find out what’s going on if information is actually hidden. So disclosure is a necessary condition for transparency. But it’s hardly a sufficient one.

I don’t have much to say about the cost/benefit trade-off of greater disclosure in pursuit of transparency. Sometimes the benefit is obvious, other times not so much, sometimes not at all.

What’s more interesting to me is how the blind pursuit of disclosure can actually reduce transparency – even reduce people’s awareness of the distinction.

Over-Disclosure

Is it possible to have too much disclosure? So much disclosure that information gets lost in the blizzard of data?

On the face of it, disclosure is the handmaiden of transparency. But if disclosure becomes the end rather than the means, if regulators and consumer advocates become fixated on indicators rather than on what they indicate, then disclosure can actually become self-defeating.

Lawyers know that massive responses to discovery requests can overwhelm opposing counsel. Cheating spouses know that the best lies are those that disclose the most truth. Consumer lenders know to fast-talk the disclaimers at the end of radio ads, much like the small print on the ads and loan statements.

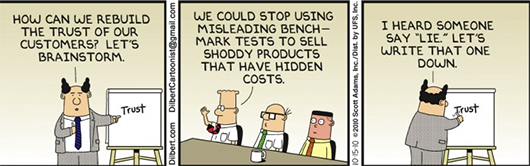

If disclosure isn’t accompanied by an ethos of transparency, it can be positively harmful. It is like crossing your fingers behind your back, taking movie reviews out of context, or word parsing a la “it depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.”

A trustworthy person, team or company will not settle for disclosure, but seek to offer transparency. A competent regulator will always remember that disclosure is just evidence, and partial evidence at that. And a wise buyer will always look for the spirit of transparency that may, or may not, underlie the act of disclosure.

Trust relies on both data and intent.