Posts

Six Reasons We Don’t Trust Wall Street

In 2013, finance is the least trusted industry globally.

In 2013, finance is the least trusted industry globally.

It hasn’t always been this way. Within the industry, it’s tempting to think that trust can be regained by reputation management. Reputation is seen largely as a function of communications or PR departments in 50% of companies in one survey.

But it goes deeper than that – deeper even than enlightened views of reputation management. There are serious structural issues that have driven down trust in the sector, and it’s hard to see how trust can be restored without directly addressing some of them.

But let’s let you be the judge of that. Here are Six Reasons we’ve lost trust in Wall Street.

1. “Wall Street” Ain’t What It Used to Be. In 1950, a discussion of “Wall Street” unambiguously meant the NYSE, the Big Board, and brokerage firms like E.F. Hutton. Today, Wikipedia says:

The term has become a metonym for the financial markets of the United States as a whole, the American financial sector (even if financial firms are not physically located there), or signifying New York-based financial interests.

That means “Wall Street” came to include commercial banking (think Chase and Bank of America), mutual funds, hedge funds, investment and trading operations like Goldman Sachs, private equity, and insurance companies like AIG. I think it’s fair to say the “new” financial businesses have had more than their share of the negative press that financial services has gotten over the years.

Many years ago, the president of GM could say – in good conscience – “What’s good for General Motors is good for America.” Can you picture Lloyd Blankfein saying, “What’s good for Goldman Sachs is good for America” with a straight face?

2. Finance Has Shifted to Zero-sum Uses. In traditional banking, borrowers create increased value with the money they borrow from lenders and put to good economic use. By contrast, in pure trading, no value is created. It is a zero-sum proposition. And the proportion of the financial sector represented by essentially pure trading has increased dramatically.

At the same time, Paul Volcker says the financial services’ share of “value-add “in the US economy grew from 2% to 6.5%. That’s not “value added” in the economic sense – it’s just an increase in price over cost. And, Volcker added, it was due not to innovation, but to increased compensation. As he famously put it, “The biggest innovation in the industry over the past 20 years was the ATM machine.”

Wall Street has increasingly focused on the “point spread,” not the fundamentals. In the NFL, they don’t let players bet on point spreads. But on Wall Street, that’s the name of the game.

The industry’s counter to such data is that they have increased liquidity, thereby lowering risk and volatility. Yet volatility in the stock market has steadily increased for decades, while the industry has gotten less efficient. And “black swans” have become part of our lexicon – we have massively underestimated risk. The value of the added liquidity is far outweighed by the risks it has entailed.

3. Finance Is a Larger Part of the Economy. In 1950, the US financial sector accounted for 2.8% of GDP. By 2011, that number had grown to 8.4%. In 2011, the financial industry generated 29% of all US profits. That proportion had never exceeded 20% in all of the 20th Century. From 1980 to 2010, the profit per employee in the financial sector of the US economy grew by over a thousand percent – far more than all the rest.

And as finance became less efficient, more profitable, and more zero-sum oriented, it also came to dominate business more. In 1937, 1 percent of the graduates of Harvard Business School went into finance. In 2008, that number hit 45%.

4. The Shift to the Short Term.

As of 2011, 60% of the daily turnover in US stock markets was accounted for by high-frequency trading something that didn’t exist a decade before. In 1960, the average holding period for stocks on the NYSE was 8 years. By 2010, it was down to 3-4 months.

In 1950, the marginal tax rate was 85%, putting a brake on short-term trading, since capital gains taxation of 25% kicked in only after 6 months.

A short-term mentality has always plagued the US in comparison to Europe and especially Asia. The shorter the timeframe, the more focused we become on transactions, and the less value we place on relationships. And that kills trust.

5. The Transactionalization of Finance. J.P. Morgan once said, “A man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.” For several years now, we’ve had the IBGYBG problem on Wall Street: “I’ll be gone, you’ll be gone – do the deal, who cares.”

Can you say “moral hazard?”

In the Christmas movie It’s a Wonderful Life, local employees of a local bank lend mortgage funds to local borrowers, with the bank then holding the mortgage itself. By 2007, the lending was done by non-local employees of non-local mortgage companies who then resold the mortgage to non-local banks, who then securitized and sold to global investors. A relationship business had become thoroughly transactionalized. This drives down trust.

6. The Attack on Regulation. The LIBOR rate-rigging scandal shocked everyone last year. But rate-rigging turned out to be not a bug, but a feature. The chairman of the CFTC said LIBOR rates “are basically more akin to fiction than fact.” The truth is more like the Wizard of Oz saying, “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

It’s a market that turned out to be mythical – can you say “Bernie Madoff?”

The Glass-Steagall Act was repealed in the late 90s, arguably giving free reign to bankers to misbehave. The industry has fought consumer legislation governing things like credit card costs, not to mention the mix of Dodd-Frank rules.

It’s hard to trust an industry which visibly and without much embarrassment argues for more and more, after the rather remarkable feast of the last two decades.

The solutions to trust issues that I hear about most coming from the financial services industry tend to be reputation management and personal trustworthiness. I do believe that both these tools – especially personal trustworthiness – could be applied to great effect in certain financial sectors – notably financial planning, wealth management, traditional investment banking, and commercial lending.

But that’s not where the money is, nor where the biggest problems lie. And it’s going to take a whole lot more than the usual approach to reputation management to deal with them.

Until the sector can address those six areas of structural disconnect, the issues of trustworthiness will continue to dog the industry.

S&P and the New Challenge of Integrity in Business

We’ve all read tales of corporate wrongdoing – think Bernie Madoff, Enron, LIBOR. In most cases, managers engaged in nefarious behavior, knowing they were doing wrong. There are a few cases where the miscreant could plausibly argue ignorance, or good intentions – Martha Stewart, perhaps.

But a recent courtroom defense by Standard & Poors in response to a Federal charge of fraud, opens up a whole new threat to corporate ethics.

Subordinating Ethics to Legal Arguments

Back in April, S&P responded to a Justice Department’s complaint that S&P’s claims of ratings objectivity, independence and integrity were false, and part of a scheme to defraud investors.

S&P’s creative approach was to argue that such statements were only “puffery,” and that a reasonable investor would not depend on them.

Let’s underscore this. S&P, as a legal strategy, decided to disavow its own declarations of objectivity, independence and integrity, saying in effect, “everyone knows we’re just blowing smoke.”

- Picture Boeing saying, “About that 787 safety stuff – you didn’t really think we were serious, did you?”

- Picture Legal SeaFood saying, “Oh, you thought we meant genuine bluefish? Ha ha, silly you.”

- You get the picture.

This is not a company trying to avoid being caught. It’s not a case of extenuating circumstances, or offsetting benefits. It is not even arguing an interpretation of what is wrong.

S&P is arguing – as part of a legal strategy – that “integrity” is just a marketing tool. This subordinates “integrity” to both marketing and legal considerations. It puts it somewhere on a par with market research or creative ad spots.

The Name of the Problem

It’s not just S&P that is confused – the media is implicated too. In his Bloomberg News story on the issue, Jonathan Weil characterizes the problem this way:

The problem is that sound legal strategies sometimes create public-relations nightmares…Often PR and legal professionals end up pursuing conflicting agendas if they don’t work cooperatively. There’s an old test that everyone in the public eye should use when making important decisions: How would this look if you read about it on the front page of a major newspaper or website?

Where S&P’s lawyers confuse ethics and legal arguments, Weil is reducing ethical issues to ones of reputation and PR.

At least Bernie Madoff had a moral compass. He knew what he was doing was wrong, and tried to hide it. But if “integrity” is a marketing tool, justified by ROI or PR, then we are in uncharted waters.

A Simple Problem

This should not be hard to manage. If someone brings a legal strategy of “integrity as puffery” to the Chief Counsel or CEO, this is what they should say in response:

“Excuse me – you are deeply confused. This is not a legal or marketing strategy issue. There will be no analyses of riskiness, ROI, or trade-offs with reputation. Integrity is not something we bargain with. It is a core value. That means precisely what it says.

“Throw away immediately any work you were doing in that direction. And I want to know tomorrow at 9AM, in writing, why it was you were even thinking in this misconceived direction. Am I clear?”

Which would you trust? A company with leadership that answered this way? Or a company that went to court with integrity for sale?

Judge Carter, who heard the case, was clear:

The court cannot find that all of these ‘shalls’ and ‘must nots’ are the mere aspirational musings of a corporation setting out vague goals for its future. Rather, they are specific assertions of current and ongoing policies that stand in stark contrast to the behavior alleged by the government’s complaint.

Exactly.

Too Big to Trust? Or Too Untrustworthy to Scale?

This will be my fourth week on the road; more on that later in the week. At least all that plane time (and waiting in lines time) makes for good reading time—thanks to the iPhone Kindle Reader app. (and no they don’t pay me for saying it).

I’m re-reading Francis Fukuyama’s 1995 classic Trust: the Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity.

It’s the perfect companion for Andrew Ross Sorkin’s Too Big to Fail: The Inside Story of How Wall Street and Washington Fought to Save the Financial System—and Themselves.

Fukuyama’s View of Trust

Fukuyama makes a compelling case that economic development is strongly affected by the cultural norms of a society—in particular, the propensity to trust. In this, he is up against both neo-classical economists (who argue people are rational utility-maximizers), Marxians (who argue it’s all about the money), and a ton of management theorists (who pretty much believe both).

The Chinese, Korean and Italian preference for family, Japanese attitudes toward adoption of non-kin, the French reluctance to enter into face-to-face relationships, the German emphasis on training, the sectarian temper of American social life: all come about as the result not of rational calculation but from inherited ethical habit.

Who we trust, it turns out, radically determines the nature of business we engage in. He explains why large French companies are state-owned, and why Chinese companies find it hard to hire professional management (think Wang Laboratories).

Fukuyama describes several cultures in the world–southern Italy, chunks of Russia, some Chinese regions—which contain high-trust pockets of communities within a broader society of low-trust intermediate institutions.

Those high trust pockets? Think the Mafia, Chinese tongs, and street gangs.

Their values? Fierce loyalty toward each other, coupled with a level of competitiveness bordering on paranoia regarding other competing pockets and the world at large.

Too Big to Fail?

Andrew Ross Sorkin’s book is riveting reading, a blow-by-blow account of who said and did just what to whom during the extraordinary market meltdown that brought down Lehman Brothers, resulted in the TARP legislation, and nearly brought the world financial system to a full stop.

Part of the charm is sorting out the black hats and the white hats; maybe I should say black and shades of gray.

Paulson and Geithner emerge as the flawed heroes. Jamie Dimon plays to the crowd, but is also the only really good manager of the lot, and the only one to show flashes of true industry leadership and something resembling responsible social behavior.

The rest, frankly, resemble refugees from a failed Sopranos casting call. Jimmy Cayne, John Mack, and Dick Fuld in particular come off as mob leaders, with Goldmans’ Lloyd Blankfein coming off better only because of a better sense of a world beyond New York.

Wall Street as Low Trust Culture

The majority of suggestions to reform Wall Street focus on four solutions:

1.structural cures (e.g. separate investment and commercial banking functions),

2.regulatory cures (e.g. prescriptions for capital ratios),

3.enforcement (e.g. tougher sanctions, more investigative staff for the SEC),

4.compliance (more procedures).

None of those critiques draw the conclusion that feels obvious if you’ve just read Fukuyama: that the dominant model of leadership on Wall Street has been pretty much like the Mafia—or the Sopranos, anyway. Wall Street has been run by a cabal of low-trust, tribal, familistic gang leaders.

The inability to work as a group when the industry was threatened; the tendency to circle like cannibalistic sharks when there’s blood in the water; the pathological obsession with ‘enemies’ (the most hated being the short-sellers, who as near as I can tell were never shown by anyone to have done any significant harm and who in fact did a lot of good, but were nonetheless the villain of choice); the celebration of loyalty coupled with the ability to flip allegiances on a dime. All these are traits of low-trust cultures.

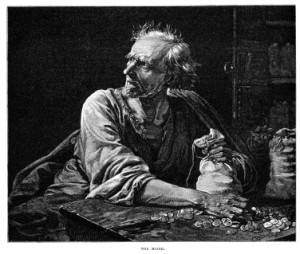

A trader once told me how he was recruited.

“The guy from [Big Wall Street Firm] walked into a room of 25 expectant recruits, and said, ‘Who here is motivated by fear and greed?’ Me and another guy raised our hands timidly. ‘The rest of you can go home,’ he said, ‘I’m only interested in these two.”

So how do these clowns get so much power? Amid all the defeatist models that posit human beings as innately susceptible to money, that assume selfish motives are immutable and can only be beaten by more rules and rewards, I still think there is a valid role to be played by culture and character.

There are more than a few moments of perspective, responsibility and decency shown in Sorkin’s book by Geithner, Paulson and Dimon. Why aren’t there more players like them?

In Sorkin’s final pages, he warns that we’re already letting the opportunity for genuine reform slip by—and not just regulatory and structural reform either. But, he says:

Perhaps most disturbing of all, ego is still very much a central part of the Wall Street machine. While the financial crisis destroyed careers and reputations, and left many more bruised and battered, it also left he survivors with a genuine sense of invulnerability at having made it back from the brink. Still missing in the current environment is a genuine sense of humility.

Whether an institution—or the entire system—is too big to fail has as much to do with the people that run these firms and those that regulate them as it does any policy or written rules.

Amen to that, Mr. Sorkin. We cannot afford these low-trust types wandering around with their hands on the financial world’s throat.