It’s an article of faith in business that “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” The alternative phrasing is, “What gets measured gets managed.”

Nowhere are those mantras more repeated than in the fields of corporate sales and training. And at the intersection—the field of sales training—it’s beyond an article of faith; it’s more like The Book.

And yet, in my admittedly limited experience (serving mainly high-end, intangible, B2B businesses), I’ve noticed very curious things:

- Learning and development organizations want to see precise, detailed performance metrics in their sales training programs, and they request evidence of such metrics from vendors’ past client engagements.

- Those same companies do not themselves have such metrics for past training programs – and they balk at the opportunity to create them when offered.

- Those companies feel guilty about this disparity.

They shouldn’t feel guilty. There’s a reason none of them actually produces the metrics they claim to want—because the metrics they want are the wrong metrics. Furthermore, the act of measuring them is harmful.

Companies for the most part end up doing the right thing despite their “best thinking.” Like Huckleberry Finn, who felt himself a sinner for having helped the slave Jim escape to freedom, learning and development departments are not sinners at all—they’re actually doing the right thing.

In this article, I’d like to congratulate them for their “failure” and point out an alternative to the wrong thinking they’ve been holding themselves accountable to.

The Heisenberg Principle of Training

In physics, the Heisenberg Principle says that at the sub-atomic level, the act of measuring either mass or velocity actually changes either the velocity or the mass. In other words, measuring affects measurement.

What’s true at the micro-level in physics is true at the higher-order level in business training—the training of skills in areas such as engagement, vulnerability, listening, trust, empathy, or constructive confrontation. In those areas, the act of measurement affects the thing being measured. That effect can be positive or negative.

It does matter that you measure. What also matters, however, is what you measure and how you measure it – and we think wrongly about each.

It goes wrong when we approach these higher-level human functions as if they were lower-level behavioral skills. We apply the same mindset to them that we successfully apply to learning a golf swing, developing a spreadsheet, or creating a daily exercise habit.

These higher-level arenas evaporate when we subject them to the relentless behavioral decomposition appropriate for lower-level skills. Consider an example:

You declare to your spouse your commitment to improving your marriage. Your spouse is happy to hear of this decision until, that is, you declare that “obviously” you need a baseline and a set of metrics to regularly track your improvement. Still, your spouse is a team player and grudgingly agrees to go along. You jointly assign a 79.0 basis (on a 100 scale) for your baseline quality of marriage.

All goes well the first week: you are mindful of taking out the garbage, looking away from your email when your spouse speaks to you, and asking “how are you?” at least once a day—until measurement time. You then ask your spouse to rate your progress at the end of week 1: “Do you think I’ve moved the needle from 79.0? Maybe up into the 80s, huh?”

At this point, your spouse declares the experiment over, suggesting that you don’t “get” the whole concept. Oops. And by the way, you just slipped below 79.

What went wrong? On one level, it trivializes marriage to describe it solely in terms of behavioral tics like taking the garbage out, even though in the long run there is clearly a correlation. Further, focusing on taking the garbage out suggests it’s a cause rather than an effect. Finally, the frequency of focus on such things forces attention away from the true causes and drivers—a mindful attitude.

And on a deeper level, treating measurement this way confuses ends and means. A good marriage should be rewarding on its own terms. The overlay of a report card raises ugly questions: From whom are you seeking approval? And approval of what? Why, after all, are you doing this in the first place? What does “success” at the scorecard add to success in the marriage?

Gamification, so useful in more plebeian aspects of life, is trivializing, even insulting, when applied to the game of life.

Want proof? Ask your spouse.

Errors in Training Measurement

Such measurement is also trivial when applied to higher-level sales training. It’s true that to be successfully trusted as a salesperson, you need to do a great job of listening, empathizing, telling the truth, collaborating, and focusing on client needs. And if you do all of those things, you will sell more.

But the higher sales come about because you focus on the relationship. The sale should be a byproduct of a relationship – not the purpose or goal in itself, with the relationship solely a means to the sale. Focusing solely on the byproducts sends exactly the wrong message.

There are two errors you can make:

- Measuring those improved sales every week (or very frequently). Doing so proves to everyone that you really don’t care about all of that empathy and trust stuff except insofar as it improves sales. Which means you’re a hypocrite. Which means they won’t trust you and won’t buy from you. Hello Heisenberg.

- Measuring the constituent behaviors. If you break down “empathy” into various behaviors (looks deeply into client’s eyes, pauses 0.4 seconds before answering questions, uses phrases like ‘that’s got to be difficult’ at least once per paragraph, etc.), it proves to everyone that you don’t “get” empathy. You are just a mimic, and not a terribly good one at that. Which means they won’t trust you, and won’t buy from you. Hello Heisenberg, again.

Using Measurement Positively

Up until now I’ve been negative about the ways measurement is used—actually, the way we talk about it being used—because in fact, our better instincts take over and we don’t actually do these things often. But there are positive ways to measure. There are three principles:

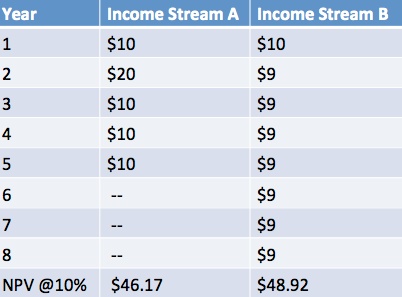

- Pick long-term, big picture metrics. The best one for sales training is, of course, revenue—but measured over time. The right timeframe varies with the business, but less than quarterly is too much.

Other things you could measure—and there shouldn’t be too many—include account penetration, share of wallet, or cost of sales. Again, these should be looked at as trailing indicators of performance, avoiding any suggestion that they are short-term causal drivers to be tweaked. You don’t cause mindsets like trust by practicing tiny behaviors; you cause tiny behaviors by focusing on mindsets like trust.

- Substitute discussion for reports. If your only reason for metrics is to “manage” them, then everyone will intuit your bad faith—that you don’t really care about empathy, you care about winning the battle for being empathetic as soon and as profitably as possible, and you will ding anyone for not being empathetic.

Instead, have irregular but frequent open-ended discussions about the numbers. There’s nothing wrong with discussing listening techniques or examining pipeline status. Doing so is how we get better and should be the purpose of sales coaching. But by discussing rather than “reporting” and “evaluating,” you show that your purpose is indeed on the end game (engagement, trust, etc.) and not on scorecards.

- Publicize discussions as motivation, not metrics. If someone has a breakthrough in listening, use the process to celebrate and educate the organization. (Look at what Joe did, and how he did it!) This is using Heisenberg in a positive way—to publicize insights and to encourage.

The alternative—defining smaller and smaller behavioral details—whether you publicize it or not, sends the message that salespeople are being evaluated, not coached. It also says that the metrics matter, not the end purpose they’re intended to serve.

Learning and development people: stop thinking you need detailed behavioral metrics. Give yourself a break, give your vendors a break, and give your salespeople a break. Coach your staff, demand principled behavior from them, and hold them accountable. Don’t track them minutely and with an hourglass. Coach on details to get better, measure end results to show it’s all working, and communicate what’s important.

The ZDNet headline is striking: “

The ZDNet headline is striking: “

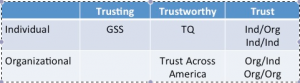

How can you measure trust?

How can you measure trust?