A Tale of Two Cities: Trust and the iPad

Suppose you’re a high school administrator in a metropolitan area. Your district has the opportunity to use a number of iPads at subsidized rates to help in the students’ education.

Suppose you’re a high school administrator in a metropolitan area. Your district has the opportunity to use a number of iPads at subsidized rates to help in the students’ education.

Would you:

a. Be sure to load up the tablets with educational software and put in some restrictions on social media sites,

or,

b. Leave the devices pretty much the way they are out of the box, with no particular restrictions?

This happened. One district was in Los Angeles; the other, Burlington Mass, a suburb of Boston. The question du jour is:

Which school district went with which approach?

So Much for Laid-back West Coasters

Westchester High, part of the Los Angeles Unified School District, went with option a. Let’s just call it, oh, the “We don’t trust you kids” option.

Burlington (in the heart of Boston’s famed Rt 128 tech corridor) did the loosey-goosey thing.

So much for east coast / west coast stereotypes.

But what’s interesting was the result.

The Fruits of Low Trust

Students in LA took only a few days to hack the filtering software, thus getting into the verboten territories of Facebook and Pandora. The school district:

treated the security breach as a crisis. At Westchester High and two other schools where students managed to liberate their iPads, it ordered that all tablets be returned. In a confidential memo intercepted by the Los Angeles Times, LAUSD Police Chief Steven Zipperman warned of a larger student hackathon and suggested the district was moving too quickly. “I’m guessing this is just a sample of what will likely occur on other campuses once this hits Twitter, YouTube, or other social media sites explaining to our students how to breach or compromise the security of these devices,” wrote Zipperman. “I want to prevent a runaway train scenario when we may have the ability to put a hold on the rollout.

There are plenty of folks who see the LA experience as a fiasco, serving the interests only of tablet producers like Apple.

The Payoff of High Trust

But then there was Burlington. Other than installing a porn filter, the district consciously chose to avoid the “lockdown” approach, instead offering “digital literacy” classes where kids could develop a web presence to impress college admissions officers.

The students already intuitively knew how to use the equipment. They took to it like ducks to water, rapidly outpacing the faculty, who then dug in to catch up with their students.

The teachers now go to a student-run Genius Bar. The English department created an online vocabulary textbook that saved budgeted funds. And the kids behaved themselves.

The program was enough of a success that they’re expanding it to middle school students.

The Moral of the Story

Too often when we speak of trust, we speak only of static components – moral values, credentials, observing rules. But an enormous amount of trust is governed by the reciprocating, interactive rules of human behavior.

Specifically – one of the best ways to make someone trustworthy is to start by trusting them in the first place. People hugely live up – or down – to what is expected of them. So much of the cure for low trust lies not in yet-more regulations and audits, but in more risk-taking that requires trust!

Are you listening, banks? HR departments? Employment lawyers? Teachers? The cure to low trust is frequently – more trust.

The headlines, surveys and news stories are everywhere. Trust is down – in world leaders, in legislatures, in financial institutions, doctors, even religious leaders and educators. It is very, very easy to draw one conclusion from all this – that we have a crisis of trustworthiness.

The headlines, surveys and news stories are everywhere. Trust is down – in world leaders, in legislatures, in financial institutions, doctors, even religious leaders and educators. It is very, very easy to draw one conclusion from all this – that we have a crisis of trustworthiness. This is the third in a four-part series about why we don’t trust companies. The final post will offer solutions.

This is the third in a four-part series about why we don’t trust companies. The final post will offer solutions. People don’t trust companies very much.

People don’t trust companies very much. I always have trouble answering a question I’m often asked: What company does a great job on trust? Because the answer is some combination of, “it depends on the definition of trust,” and “hardly any.” Let me unpack that.

I always have trouble answering a question I’m often asked: What company does a great job on trust? Because the answer is some combination of, “it depends on the definition of trust,” and “hardly any.” Let me unpack that.

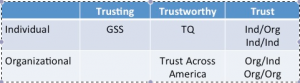

How can you measure trust?

How can you measure trust?