Ralph Catillo is an Account Executive with Gallagher Benefit Services, one of the largest employee benefit agencies in the northeast region of the United States. Read Ralph’s no-holds-barred replies to questions about what it really takes to be a trusted advisor—and how the lessons he has learned apply at home as well as at work.

Ralph Catillo is an Account Executive with Gallagher Benefit Services, one of the largest employee benefit agencies in the northeast region of the United States. Read Ralph’s no-holds-barred replies to questions about what it really takes to be a trusted advisor—and how the lessons he has learned apply at home as well as at work.

First Impressions

I know Ralph because he was a champion for a Trusted Advisor immersion workshop I led for his company in 2010. The first time we ever spoke on the phone, I was immediately struck by two things about him: his humor and his candor. Within minutes of interacting with Ralph, it’s crystal clear that he has nothing to hide. You get the sense that he’s quick, yet not in a rush; he’s knowledgeable, yet more interested in what you have to say than what he knows.

I began the interview for this article by asking Ralph a simple question: What does it take to be a trusted advisor? With characteristic dry wit, he immediately said, “I show up with a brown bag full of cash. It’s all been laundered.” Then he got serious for a moment, because more than anything he’s a thoughtful guy. His answer was simple: it takes honesty and purpose.

The 1-2 Punch of a Trusted Advisor: Honesty and Purpose

“You have to be 100% transparent, and 100% with no agenda other than doing the right thing. That’s really all there is. If you put aside your agenda, and your role, and really just come from the perspective of what is the best thing for this situation, whatever it may be, then you’re on the right track.

“The challenge is, the best thing for this situation might not be clear from the onset. So you have to get comfortable being in a zone of not knowing, where others are sometimes uncomfortable, and just put it all out there. You don’t have to have the answer, and you definitely don’t have to be the smartest one in the room. Everyone—me included—gets tripped up trying to be the smartest in the room, as opposed to coming at it with open ears and eyes. The best idea usually comes when you don’t come at it from an angle.”

As for honesty, Ralph says, “We’re in the services business, so it’s all about relationships. You have to be yourself. When you’re not, it’s unhealthy and unproductive.”

I asked Ralph about the courage it takes to do what he prescribes. He laughed. “Courage? I think it’s a lot more courageous to try to skirt an issue or be someone you aren’t—you put yourself at much greater risk. If I put all my cards on the table and I don’t get the business, well, at least I know I did everything I could.”

Nature or Nurture

I asked Ralph if he came by his approach naturally, or if he had learned it over time.

“I’ve evolved to it. When you’re in school, you’re trained to get the right answer. No one teaches you how to have conversations and day-to-day interactions. Then you take that right-answer mindset into business and it doesn’t work. In fact, that’s why I think so many managers struggle and fail—because they try to force what they think is right on others.

“I’ve definitely butted heads with people a lot along my own learning curve. Fortunately, I had a great role model and mentor along the way.”

Mentoring and Stewardship

Ralph credits David Friedman with his mindset about building trust in relationships. David, who joined his father and a part-time secretary 28 years ago in a small insurance practice located above a storefront on Main Street in Moorestown, NJ, later became the company’s first and only President when they incorporated as RSI in 1994 (later merging with Gallagher). Ralph says, “My first foray into trust-based relationships was through the RSI Fundamentals, which David created.”

The Fundamentals, which have since been published as a book, are 30 tenets that inform every employee’s day-to-day behavior. They include directives like:

- Work from the assumption that people are good, fair, and honest.

- Create a feeling of warmth and friendliness in every client interaction.

- Take responsibility.

- Be quick to ask and slow to judge.

“Those 30 Fundamentals changed my whole thought process and approach. Because of the Fundamentals, we’re deliberate about the mindset we bring to our interactions. We use a common language. And we have the right people too—we’re careful about hiring.”

Ralph credits David for David’s personal mentoring and stewardship of Gallagher Benefit Services. “It’s thanks to David that our company has developed and sustained this kind of culture. I’m not a lone ranger in my organization; it’s a top-down thing. That doesn’t mean it isn’t sometimes a challenge. It’s still uncomfortable to walk the talk, and not everyone is great at it. But at least we have a shared understanding about what we aspire to.”

It’s Business; It’s Personal

Ralph sees a lot of parallels between trust in business relationships and in personal relationships.

“Consistency breeds trust. I see that as a professional, as a friend, and as a father. With my kids, all I want them to do is communicate, without fear of repercussions. That takes a lot of time and experiences and leading by example.

“Just yesterday my teen-aged son had his buddies over after school, before I came home from work. They’d come from the pool, and one of my son’s friends sat in my chair in his soaking wet suit. As soon as I got home, my son pulled me aside, told me what happened, and took responsibility for it. He was surprised when I thanked him for being up front and direct about it, instead of getting angry. I reminded him what I want more than anything is for him to just keep talking to me. A chair is a chair; it can be cleaned up. But the next time it might be something far more worrisome, like someone approaching him with drugs. I want to be a parent, and a resource, not the judge and jury.”

Keeping it Simple

Ralph’s perspective on leading with trust in all his relationships is a lot like the guy himself: uncomplicated, direct, thoughtful, real.

In the words of the famous artist, Leonardo DaVinci, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” Thank you, Ralph, for sharing your art with all of us.

Connect with Ralph on LinkedIn.

—————————————————

The Real People, Real Trust series offers an insider view into the challenges, successes, and make-it-or-break-it moments of people from all corners of the world who are leading with trust. Check out our prior posts: read about Chip Grizzard, a CEO You Should Know.

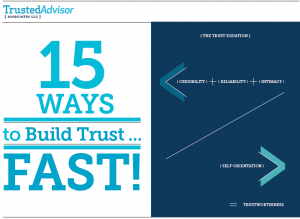

In case you missed it, here’s your opportunity to get a copy of our latest eBook, “15 Ways to Build Trust … Fast!”

In case you missed it, here’s your opportunity to get a copy of our latest eBook, “15 Ways to Build Trust … Fast!”

From Delta Airline’s Website,

From Delta Airline’s Website,  Ralph Catillo is an Account Executive with

Ralph Catillo is an Account Executive with  We’re about halfway through our countdown of Trust Tips leading up to the release of “The Trusted Advisor Fieldbook: A Comprehensive Toolkit for Leading with Trust,”

We’re about halfway through our countdown of Trust Tips leading up to the release of “The Trusted Advisor Fieldbook: A Comprehensive Toolkit for Leading with Trust,”  It was five months ago, but I remember it like yesterday.

It was five months ago, but I remember it like yesterday. What would you do?

What would you do? Don’t you hate the “IF” in that phrase? It’s like the

Don’t you hate the “IF” in that phrase? It’s like the  Supposed you asked me the score of the latest Boston Red Sox vs. New York Yankees game, and I told you “12.”

Supposed you asked me the score of the latest Boston Red Sox vs. New York Yankees game, and I told you “12.” Pat’s story…

Pat’s story… They wanted to sell a used truck. My son wanted to buy one for his business. He asked me to come along to help negotiate.

They wanted to sell a used truck. My son wanted to buy one for his business. He asked me to come along to help negotiate.