What’s the role of listening in the sales literature? Here are two examples culled from internet searches:

Successful sales are based on discovering what customers need and providing solutions to these needs. Always focus your questions on moving toward a greater understanding of your customer’s needs.

The secret to selling like a professional is to listen closely to the client. Find out as much as possible that might be relevant to your service. Ask questions about their expectations. Then when you have that knowledge, discuss only the aspects of your service that have a direct bearing on your clients stated needs.

By this view, listening is a key step in a sales process. We listen in order to discover needs. Having discovered the needs, we can then better tune our offerings, or our presentations, to those needs. This allows us to screen out unlikely prospects (improving efficiency) and to better address good prospects (improving effectiveness).

That’s the conventional wisdom. It probably sounds so obvious as to border on the banal. But occasionally, conventional wisdom is wrong. And this is one of those cases.

The greatest value of listening lies not in what is heard, but in the act of listening itself.

To see why, let’s explore the conventional wisdom.

There are three key assumptions in the conventional approach. Every one of them is misleading, and at least partly wrong. They are:

- Selling is about transactions, or about multiple transactions in sequence;

- The purpose of listening is to find out information—in particular, needs;

- The buyer has this information.

In truth:

- Selling is best understood (and done) by anchoring transactions in the context of relationships—not by treating relationships as a phase in a transactional process;

- The value of listening goes well beyond “finding out data;” its greatest value is in disposing the client to engage differently with both the salesperson, and around his or her needs;

- The assumption that the buyer is conscious of his or her needs and will part with them if artfully asked the right questions is a flawed assumption. Buyers aren’t fully conscious of their needs, aren’t necessarily disposed to reveal them, and direct rational inquiry is not the best route to either raised consciousness or enhanced revelation.

Let’s break this down to two issues—sales process models (how we think about selling) and buyer psychology (how buyers think about buying).

SALES PROCESS MODELS

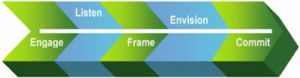

Sales models are ubiquitous in corporate selling. CRM systems are built around them. Sales management is driven by data surrounding them. But almost all sales models are simple linear, sequential models—usually depicted as arrows. Early on in those arrows, we find listening.

The role of “relationships” in those arrows is either non-existent (the model depicts purely transactional sales “events”), depicted as a feedback loop (“go back and repeat from point B”), or is contained in the early-stage process listening step (“listen until rapport is formed; than move to needs-based questioning.”)

But that’s not how it really works. In the real world, relationships function as a substrate, a precondition, a context. Except for a purely cold call, sales do not happen in a vacuum. Farmers don’t plant seed in untended soil, no matter how fertile the ground. They plow it, turn it, fertilize it, water it, and wait for just the right time to plant. That is how really good salespeople treat relationships.

Really successful salespeople are always establishing and deepening relationships with people. Doing so earns them the right to engage in a different form of conversation, around a buyer’s needs and around selling. They use that right with some and not with others; and they use that right at once with some, and later with others.

A really successful salesperson builds relationships with some who may not end up buying. They may build a relationship with someone and engage in selling at a later date.

If you think the “purpose” of building a relationship is to lead you along a process of selling the client, then you are likely to ask questions in order to get answers. Your idea of “listening” will be in service to driving the process model forward.

And your prospect will get the same idea: “He’s listening to me in order to find an opening to best present whatever he’s selling. I’ll go along ias long as it suits me, but I’m on my guard.”

By contrast, if you think the “purpose” of building a relationship has a much looser connection with a sales transaction, then you are likely to ask questions more out of curiosity, aimed solely at getting to know the person or understanding the broader business context—without a specific agenda, transaction or “opening.”

And your prospect will get the same idea: “He’s listening to me genuinely, with some interest in me and in how I see things. This is good, he’s coming to understand me on my terms, not to sell me something. I’m willing to continue talking.”

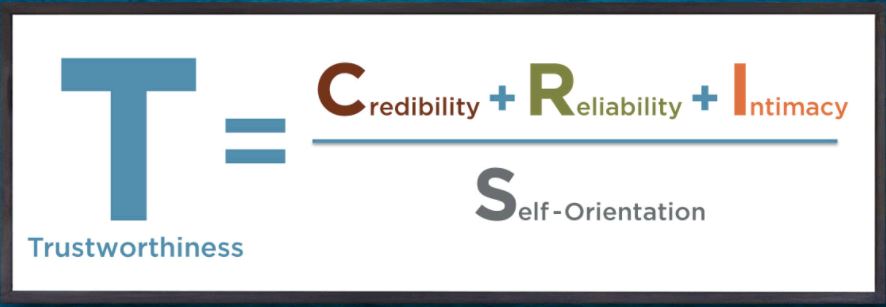

If you work from a linear process model that makes listening a tactic to achieve a transaction, then you are only listening to hear your pre-conceived ideas. You are, in a nutshell, self-oriented. That is seller-centric selling. And it doesn’t promote trust.

BUYER PSYCHOLOGY

Ask a client what they want, and they’ll tell you “expertise; credentials; someone who’ll meet my needs.” Ask them what their needs are, and they’ll tell you.

But ask really successful salespeople (or honest clients with experience in buying) and they’ll tell you how it really works. Clients only ask for credentials and expertise because they’re not really sure what else to do. In truth, they’d rather get in range with expertise, and then decide based on their trust in the seller.

Clients will tell you their needs because they think they’re supposed to, and because they’re afraid if they don’t, you’ll take advantage of them. But if you can engage them in honest discussion, they’ll admit their uncertainties, and discuss, engage in and evolve their views of what their needs are.

It all depends on why you’re listening.

If you’re listening to hear an answer to a predetermined question, then you will hear the “canned” definitions of needs that clients have prepared for you. You’ll hear their request for credentials and expertise at face value, and not hear the undertone in the question, or in the bored way they listen to your answer.

Because what clients really want to talk about is what everyone wants to talk about. Themselves. When someone says, “tell me about yourself,” they’re just being polite—whether it’s on a date, at a social event, or in a sales call. The right answer is not to tell them about your vast experience with other clients—it is to get them talking about themselves. And to listen as they do so.

THE QUALITY OF LISTENING

The usual form of listening is conditioned by sales models looking for answers, and by flawed views of buyer psychology focused on surface dialogue. What is required is a different quality of listening.

The main reason for listening to customers is to allow the customer to be heard. Really heard. As in, actually being paid attention to by another human being.

This kind of listening is listening for the sake of listening. Listening to understand, period—no strings attached, no links back to your product, no refined problem statements. Because that’s what people in relationships, at their best, really do. They listen because they want to know what the other person thinks. About whatever the other person is interested in talking about.

This kind of listening validates other people. It connects us to them. It provides meaning. And—among other things—it sets the stage for sellers and buyers to interact—if that is the right thing to happen next.

Brooks and Travesano (“You’re Working too Hard to Make the Sale”) note that people greatly prefer to buy what they need from those who understand what it is that they want.

Read that over again, carefully. People prefer to buy what they need (stuff they’re going to buy anyway), from those who understand them on the basis of what they want (things in life they’d love to have—wishes, hopes, desires.)

You don’t even have to give them what they want; it’s enough to understand them.

To bring it full circle back to listening: Relationships are the context for successful selling. Relationships are based on trust; they predispose us to engage in qualitatively different kinds of sales conversations. And listening—unrestricted, unbounded, listening for its own sake—is the way we develop such relationships.

And therein lies the paradox. The most powerful way to sell depends on unlinking listening from selling—and instead, just listening. Listening not as a step in a sales process, and not as a search for answers to questions. Listening not as a means to an end, but as an end in itself.

The point of listening is not what you hear, but the act of listening itself.

MAKING IT WORK

Here are 5 tips to listening this way. Number five is the most powerful.

1. Ditch the distractions. You cannot multitask undiscovered. Being multitasked feels insulting. Close the door. Face away from the window. Blank the computer screen. Turn the blackberry over. Now—pay attention.

2. Use your whole body. Lean toward the speaker—even on the phone. Use facial expressions. Use hands and arms, shake your head, use ‘non-verbal’ verbals. This improves your listening—and indicates you are listening.

3. Keep it about them—not you. Use open-ended, not closed, questions. Let them tell their own story—don’t use them as foils for your hypotheses.

4. Acknowledge frequently. Paraphrase data, empathize with emotions. Make sure you are hearing both correctly; make sure they know you are.

5. Think out loud. The biggest obstacle to listening is your own thinking. Be courageous—postpone your thinking until they’re done talking. Be willing to think out loud—with the client. Doing so role-models collaboration and transparency, which reinforces trust. I hear you. I value you. I respond to you, with no hidden agenda. I trust you. You can trust me.

That’s the message of listening.

The way most of us would view having to handle snakes.

The way most of us would view having to handle snakes.