Create Trust, Gain a Client

Nothing improves business development more than gaining the trust of the potential client. Yet few consultants do what it takes to be trusted. We sell in ways that destroy rather than create trust because we misunderstand the buying decision.

Clients talk as if they focus only on features and price, but that’s not how they really decide. In contrast to the one-dimensional, linear models of the sales process that we all learn, their decisions are the result of a two-step process. The first step is screening, which is done fairly rationally. But the second step, selection, is much more emotional. Clients are not just rational decision makers calculating discounted present values and minimizing downside risk. They are also human beings, and human beings buy with their heart and then justify it with their head.

Our Errors

We undermine our efforts to build trust by making four basic errors:

We are overly rational. We forget that buying is an emotional as well as cognitive process. People need not only to be convinced but also to feel comfortable with their decisions. Above all, they need a consultant who listens to them.

Being right is vastly overrated. Earning the right to be right is where the action is and where most consultants fall down. An ounce of listening—paying attention, paraphrasing, conveying empathy, going where the client goes—is worth a pound of correct answers, references, and credentials.

To convince clients rationally, we must also approach them emotionally.

It’s too much about us. Clients usually ask us to tell them about ourselves.They don’t really mean it. They just don’t know what else to ask and don’t want to look ineffectual.

Imagine going out on a blind date with someone. Would you want to hear the person talk about the last 17 people he or she went out with? Of course not. Yet somehow we expect clients to be enthralled with all our past relationships. But their favorite subject is everyone’s favorite subject—themselves. Talking about ourselves doesn’t make us trustworthy. Talking about them, and particularly hearing about them, does.

Clients pay attention to us only if we first pay attention to them.

We are control oriented.Most sales training programs say to set goals for each meeting. Most consultants are delighted to take that advice. We say, “Just wait a bit, I’ll get to that in the next section.” We look at our watches when the client is talking about something other than our objective. If the client wanders to other topics, we gently but firmly bring the discussion back to our objectives. If we’re running out of time, we abandon lively client-driven conversations in order to get to our objectives. And if we walk out without our objectives achieved, we feel we have failed.

There are only two good objectives for every sales interaction. The first is to move the relationship forward, and the second is to help the client. If you have achieved the second objective, you’ve almost always achieved the first.

You gain the most control by giving it up.

We focus too much on the transaction. Most approaches to business development come from sales models for nonconsulting industries and are rooted in competition-based views of selling, in which the whole emphasis is on “getting the deal.” This is wrong for the consulting industry. Instead, the emphasis should be on “doing the next right thing for the client.” Getting the engagement becomes just another point in a developing relationship.

The best transactions happen when we do not focus on transactions but on relationships.

Our Emotional Resistance

While buyers are partly emotional, consultants are even more so. Even our resistance to the idea of selling on trust is itself largely emotional. There are several reasons for the emotional resistance that lies at the root of the sales process errors noted before.

We overrate content mastery. Most consultants work in subject areas that require in-depth technical competence. We’ve been hired, trained, compensated, and promoted almost entirely on the basis of technical mastery since the second grade. And so we reject selling based on “simple” or “soft” approaches because it sounds too “easy” or it “doesn’t seem to make sense.”

But that rejection has nothing to do with ease and everything to do with unease. We’re just not comfortable with processes that don’t depend on cognitive mastery. Our comfort zone is intellectual complexity. We distrust and are ill at ease with the messy emotional aspects of personal sales. We want to “think” our way into effective selling.

We focus too much on competition. The reigning paradigm in business is competition, not collaboration; me, not we; competitive advantage, not shared destinies. The competitive paradigm is ingrained. Think of the two most common metaphors for business: athletics and war. In neither is there a client. The very language of business reflects a preoccupation with competition. It’s difficult for anyone to leave such unconscious biases behind.

Many consultants haven’t sorted this out and are at odds with themselves. A part of them believes that selling is unethical; hence the desires for euphemisms like “business development” (phrased in the passive voice, as if to distance ourselves from any tainted intent). Those of us who feel this way become suspicious of trust, fearing that, if we use it, we might become manipulators. This view doesn’t give our clients much credit for thinking independently.

We’re unable to think paradoxically. Most consultants are linear thinkers. The ideas of dialectical logic (“we are never so alone as when in the middle of a crowd”) or paradox (“you gain the most influence by not seeking influence; to be heard, first listen”) is very difficult to accept. Paradoxes violate our comfort zone model of thinking, and thinking is something in which consultants are—paradoxically—very emotionally involved.

We cannot give up control. Most consultants desire control and dislike being controlled. But a need for control conflicts with transparency, collaboration, and client focus—three fundamentals of trust-based selling.

As long as a consultant believes the purpose of business development is to get sales (engagements), trustworthiness is at risk. The key is to reframe “sales” to mean the professional obligation of a consultant to help clients envision an alternate, preferable reality and then to help them get there. If we can see how things can be better for our clients, it would be unprofessional not to point it out to the client. That, by another name, is selling, which can be done in a way that creates trust during the business development process itself.

The Principles of Trust-based Selling

The only way to be trusted in consulting is to be trustworthy. Intent matters; there are no shortcuts. You can use the business development process to build trust by adopting the following four principles:

1. Client orientation for the sake of the client, not the consultant.

“Client focus” for the seller’s sake is the bogus focus of a vulture. True client orientation means we seek to address the client’s best interests, in the sales process as in all else. If that means another firm is best for the client, we say so, knowing that in the long run we get credit from present and future clients for being client focused for the client’s sake.

2. A medium- to long-term perspective.

Focus on the relationship, not the transaction. Perhaps we should say, “The relationship is the client.” Acting with a medium- to long-term perspective in mind also solves the usual sellers’ concern about the economics of trust: It means the economics of a particular project or transaction should be discussed in terms of fairness in the long run, rather than in competitive terms. A couple in a marriage quickly compromises on who takes out the garbage rather than belabor it to get the best deal. There is much more at stake in a serious relationship than getting the best deal in each transaction.

3. A habit of collaboration.

Business developers demonstrate trustworthiness by constantly involving the client-to-be. Don’t speculate about what clients are thinking—ask them. View the proposal-writing process as something that can be done collaboratively rather than as a competitive exercise in putting the best face forward. Value meetings over phone calls, and phone calls over letters and e-mails. Practice putting all issues on the table for joint discussion rather than negotiating from competitive positions.

4. A willingness to be transparent.

Nothing destroys client trust faster than the consultant who appears to be withholding information or trying to control the client. When you don’t know something, say so. When you haven’t got the perfect staff, say so. Be willing to be open about your pricing policies, leverage structures, and even staffing procedures. What you lose in control over perceptions is more than compensated for by the goodwill you get for being transparent.

Trust-based selling is not a sales process model but a powerful way of creating shared value for client and consultant alike. It is the application of these four principles to whatever process model you happen to use, as well as to the key aspects of business development: pricing, qualification, branding, staffing, dispute resolution, project management, and cross-selling

Addendum: How to Create Trust During Business Development

Write your next proposal sitting next to the client.

Instead of using FedEx or pdf files to submit your proposal, write it while sitting next to the client. Bring all your required information, and ask the client to do the same. Leave the room only when a joint proposal is finished, one understood by all and representing the best effort possible by one particular client and one particular consulting firm. Then detach yourself from the results, knowing you’ve done your level best to help the client.

Listen by paying attention.

A lot of what passes for listening in the consulting world is just waiting for the client to finish talking so we can start looking smart again. And, while we wait, we are thinking about what we are going to say to achieve that goal. We camouflage it through a variety of behavioral techniques—mirroring, head nods, and other nonverbal actions—but the fact is, our thoughts are elsewhere. The myth of multitasking is just that. Sadly, our clients know the truth when we nod knowingly (and absently) as they talk.

The most powerful way to listen is, very simply, to pay attention and to drop all else from the conscious mind. This does not just mean put the Blackberry away. It means stop thinking about what you’re going to do with what you’re hearing and just be there, fully, to hear what your client is saying. Period. Make listening a gift of your attention, not a skill you practice to use on others.

Think out loud.

The biggest reason we don’t listen by paying attention is that it’s scary. If we don’t think ahead, we might look silly, or worse yet, stupid. We might not be able to come up with a good idea on the spot. We might blurt out something we’d regret. We need the time to rehearse mentally. We need to put together a good response that moves the ball forward. Or so we think.

It is indeed risky, and risk taking requires courage, the courage to say, “Well, let me just try and process what you’ve told me here, uh, thinking out loud, now. Now, if what you say—I mean—no, wait, if the process time is really linked to the temperature range, like you said—didn’t you?—then, um, the temperature range also has a direct impact on customer satisfaction. I mean, isn’t that one of the implications of what you’re saying? And—well, say, how does that play in the rest of the organization? I don’t think I’ve heard others say that, is that right?”

Thinking out loud makes it clear that you’re not putting one over on them. It is the essence of collaboration; you are inviting the client to think with you, sharing even your thought process. And it is truly client focused. Not the focus of a vulture but focus for the client’s sake. Thinking out loud also increases your credibility and invites, by example, an increase in intimacy. The willingness to share the most precious thing we have, our conscious attention, demonstrates caring in the most fundamental way.

Sell by doing, not by telling.

Practice sample selling.Don’t tell clients how good you are; show them—using their issues. Don’t blitz them with credentials; demonstrate to them what your credential can do for them. People are far more impressed with actions than words, particularly actions on their behalf,

Say what you don’t know, as well as what you do know.

Many consultants try to sell by telling people how good they are. But most clients want to know about limits. They know you’re not perfect, no one is; they just want to know with whom they are dealing. Help them out, be straight with them. They will appreciate it.

Get in the habit of talking about yourself for only 90–120 seconds.

When your time is up, say, “But enough about me, let’s talk about you.” If the client wants more, give them more—another 90–120 seconds, then say, “But enough about me . . . .”

Be insatiably curious.

If you’re constantly curious, you’ll ask questions. You’ll learn. You’ll come up with great ideas. You’ll notice things. But most important, you’ll be focusing on the client, not yourself. Nothing creates genuine trust better than focusing on the client, not as a means to your ends but as an end in itself.

Vision, values, customer focus, guiding principles, trust. Those words are among the leading candidates for top business buzzwords of the last few decades. They do for eyes what Krispy Kreme does for donuts—put glaze all over.

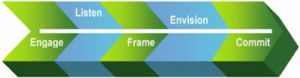

Vision, values, customer focus, guiding principles, trust. Those words are among the leading candidates for top business buzzwords of the last few decades. They do for eyes what Krispy Kreme does for donuts—put glaze all over. “We were going outside for some specialized counsel; we had reviewed the specs of a dozen firms, and really wanted top-notch capabilities. We narrowed it to three, and invited them in for 90-minute presentations.

“We were going outside for some specialized counsel; we had reviewed the specs of a dozen firms, and really wanted top-notch capabilities. We narrowed it to three, and invited them in for 90-minute presentations.