Why Your Clients Don’t Trust You – and How to Fix It

Politics has sucked up most of the oxygen surround trust recently. Now, trust in politics turns out to be a complicated matter – by comparison, trust in business is a relatively simple business. So – what about your business?

Hopefully your clients trust you more than the trust ratings of both the US presidential candidates. But – do they trust you enough? And if your clients don’t trust you enough – are you willing and ready to address that?

—

Do your customers trust you? (Be honest, now, this is not an in-house survey). Do they believe what you say? Will they cut you a break if you goof up? Are they happy to share information with you? Do they go out of their way to refer you?

Can you honestly answer ‘yes,’ to yourself, in the dead of night, to those questions?

If you’re trying to sell your services, you already know the value of being trusted. Being trusted increases value, cuts time, lowers costs, and increases profitability—both for us and for our clients.

So, we try hard to be trustworthy: to be seen as credible, reliable, honest, ethical, other-oriented, empathetic, competent, experienced, and so forth.

But in our haste to be trustworthy, we often forget one critical variable: people don’t trust those who never take a risk. If all we do is be trustworthy and never do any trusting ourselves – then eventually we will be considered un-trustworthy.

Because to be fully trusted, we need to do a little trusting ourselves.

Trusting and Being Trusted

We often talk casually about “trust” as if it were a single, unitary phenomenon—like the temperature or a poll. “Trust in banking is down,” we might read.

But that begs a question. Does it mean banks have become less trustworthy? Or does it mean bank customers or shareholders have become less trusting of banks? Or does it mean both?

To speak meaningfully of trust, we have to declare whether we are talking about trustors or about trustees. The trustor is the party doing the trusting—the one taking the risk. These are our clients, for the most part.

The trustee is the party being trusted—the beneficiary of the decision to trust. This is us, for the most part.

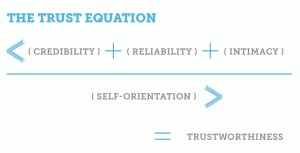

The trust equation is a valuable tool for describing trustworthiness:

But where is risk to be found? How can we use the trust equation to describe trusting and not just being trusted? How can we trust, as well as seek to be trusted?

Trust and Risk

Notwithstanding Ronald Reagan’s dictum of “trust but verify,” the essence of trust is risk. If you submit a risk to verification, you may quantify the risk, but what’s left is no longer properly called “trust.” Without risk there is no trust.

In the trust equation, risk appears largely in the Intimacy variable. Many professionals have a hard time expressing empathy, for example, because they feel it could make them appear “soft,” unprofessional, or invasive.

Of course, it’s that kind of risk that drives trust. We are wired to exchange reciprocal pleasantries with each other. It’s called etiquette, and it is the socially acceptable path to trust. Consider the following:

“Oh, so you went to Ohio State. What a football team; I have a cousin who went there.”

“Is it just me, or is this speaker kind of dull? I didn’t get much sleep last night, so this is pushing my luck.”

“Do you know whether that was a Snapchat reference he just made? Sometimes I feel a little out of the picture.”

If we take these small steps, our clients usually reciprocate. Our intimacy levels move up a notch, and the trust equation gains a few points.

If we don’t take these small steps, the relationship stays in place: pleasant and respectful, but like a stagnant pool when it comes to trust.

Non-Intimacy Steps for Trusting

The intimacy part of the trust equation is the most obvious source of risk-taking, but it is not the only one. Here are some ways to take constructive risks in other parts of the trust equation.

- Be open about what you don’t know. You may think it’s risky to admit ignorance. In fact, it increases your credibility if you’re the one putting it forward. Who will doubt you when you say you don’t know?

- Make a stretch commitment. Most of the time, you’re better off doing exactly what you said you’ll do and making sure you can do what you commit to. But sometimes you have to put your neck out and deliver something fast, new, or differently.To never take such a risk is to say you value your pristine track record over service to your client, and that may be a bad bet. Don’t be afraid to occasionally dare for more—even at the risk of failing.

- Have a point of view. If you’re asked for your opinion in a meeting, don’t always say, “I’ll get back to you on that.” Clients often value interaction more than perfection. If they wanted only right answers, they would have hired a database.

- Try on their shoes. You don’t know what it’s like to be your client. Nor should you pretend to know. But there are times when, with the proper request for permission, you get credit for imagining things.”I have no idea how the ABC group thinks about this,” you might say, “but I can imagine—if I were you, Bill, I’d feel very upset by this. You’ve lost a degree of freedom in this situation.”

While trust always requires a trustor and a trustee, it is not static. The players have to trade places every once in a while. We don’t trust people who never trust us.

So, if we want others to trust us, we have to trust them. Go find ways to trust your client; you will be delighted by the results.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] more about “reciprocal pleasantries,” from our friends at Trusted Advisor Associates, or brush up on how to accelerate trust in […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!