The Math of Low Trust

Trust in business has declined in recent years. One reason why can be demonstrated with a bit of math.

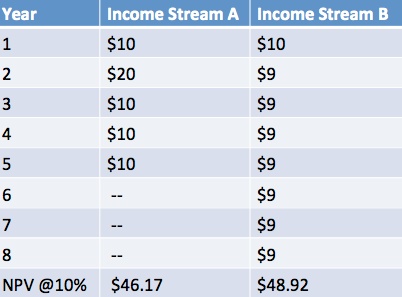

Assume two streams of income, with a net present value calculation for each. (I’ll use a 10% discount rate to simplify). Income stream A has a big payment in year 2 and then pays slightly more per year – but only for 5 years, after which it all ends.

Income stream B is steady and solid, giving less income per year – but lasting 8 years.

Which income stream do you choose? If you’re a dutiful MBA or financial manager, then in theory you choose B, the one with the higher NPV. In fact, in the real world, stream A is chosen far more often – for two reasons.

Reason 1. What if the example were ended after 7 years, instead of 8 years? In that case, the NPV of Income Stream B would drop to $44.72 – so presumably you’d choose Stream A, which is unchanged at $46.17.

Timeframe makes a difference. If the average time you spend in a job is less than 8 years, and you are a rational self-maximizing business person, you’ll choose a far shorter timeframe in which to maximize your performance, because that’s what you can control. And these days, it’s more like 2 years than 8.

Reason 2. In the above example, the unspoken assumption is that it is, in fact, a solitary single example. But assume there are thousands of investment opportunities out there, with very similar payoff characteristics. In which case the smart thing would be to take Income Stream A – and then sell it after two years. Then go find a new Income Stream A in which to invest your profits, and do it all over again. That way you’ll vastly out-perform either strategy, in virtually any time frame.

Or – would you?

Trust and Net Present Value

What’s this got to do with trust? Think back to Walter Mischel’s famed marshmallow study on deferred gratification. We do not trust people who have no self-will, who cannot defer their desire for instant gratification, because they are not in charge of their own desires. But that’s just one marshmallow incident; the rationale doesn’t go beyond Reason 1 above. What happens when one’s choices can be made over and over again?

That pattern – endlessly taking short-term gratification and jumping off onto a new high-then-low curve – is a very familiar one. It is what characterizes alcoholism, addiction, and it explains why junk food sells. “Just one more drink; one more cigarette; one more Frito. I’ll quit tomorrow, honest.” But there’s always another drink at hand, and cigarettes and Fritos are ubiquitous.

The connection to business? Easy. Think about the obsession with quarterly earnings. Think about Wall Street’s “IBGYBG” mantra (I’ll be gone, you’ll be gone – do the deal). Think sales quotas, weekly P&Ls, constantly refreshing online metrics for performance. A myriad of new front-end loaded opportunities for instant gratification. Running a business this way perverts strategy in favor of a series of opportunistic NPV calculations.

Business Since 1970 – One Major Trend

Biggest trend of the last 40 years? An obsession with markets. We have pursued, especially in finance, the grail of frictionless markets, believing that the Invisible Hand will save us by converting our individual selfishness into collective good.

It’s a crock. What markets have also done is encourage NPV calculations everywhere, all the time, and everything is monetized so we can compare them. There’s always another front-end loaded curve to buy into. Buy it and flip it. Invent a new business and IPO it before it goes profitable. IBGYBG. Markets – abetted by modularization and outsourcing and communications – have enabled massive short-termism in business.

The game works until the game doesn’t work. It works if you assume your grandchildren’s world will not suffer by your focus on short-term NPV enhancement. It works if you assume that a culture of instant monetization will beat Chinese strategies from a civilization accustomed to thinking in centuries. It works if you assume that long-term good is achieved by means of constant short-term optimization. But it isn’t.

Trust and Short-Termism

There’s a reason that one the Four Trust Principles is “Focus on the medium-to-long term, not the short term; develop relationships, not transactions.” It’s because trust is born from long-term commitments; the confidence that the other party is after something besides their own instant gratification. Short-termism is perhaps the most perniciously anti-trust business phenomenon of our times. We have been poisoning our corporate cultures through a relentless focus on markets, monetization, analytics and processes.

Those are not the basis of trust. A commitment to long-term principles and relationships is the basis of trust.