When a child is untrustworthy, parenting is needed. When an adult is untrustworthy, counseling can help. When a company is untrustworthy, markets exact discipline.

When a child is untrustworthy, parenting is needed. When an adult is untrustworthy, counseling can help. When a company is untrustworthy, markets exact discipline.

But what if an entire industry has lost trust? What kind of a problem is that? And how can it be solved?

The Banking Industry

A recent Gallup survey makes the banking industry a timely poster child for low trust. Banking is not the only low-trust industry these days; pharma could give it a good run, for example (and both are more trusted than Congress). But the trust issues raised by the poll are not just industry-specific.

First, the facts. In Rebuilding Trust in Banks, Gallup presents 32 years of survey data. That’s quite a lot of years.

In 1979, 60% of respondents said they had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of trust in banks. By 2011 that number was down to 23% (actually up from 18% in 2010).

That is a 70% decline from peak (60) to trough (18). Put another way–the industry squandered 70% of its trust. That’s quite a lot of squander.

The obvious two questions are: How does that happen? And what can be done about it?

How Can an Entire Industry Squander Trust?

I haven’t seen a single answer, partly because there is no One Answer. But I also haven’t seen a good list. So let’s break it down.

1. It’s tempting to blame a general decline in trust across all business. But there are three problems with this view:

a. Trust in business actually seems to be volatile, not steadily dropping;

b. The statistics usually conflate two issues. Saying “trust in business has dropped” fails to distinguish a decline in customers’ propensity to trust from a decline in banks’ trustworthiness;

c. There are notable exceptions. Nurses and pharmacists have topped the “most trusted professions” surveys for years–how do they beat the odds? (Particularly pharmacists–since pharmaceuticals as an industry ranks so low).

2. A decline in the inclination of people to trust. Dr. Eric Uslaner suggests that people’s propensity to trust in government is cyclical (it varies with the economy), but that trust in people has steadily declined since the 1970s.

3. A decline in general trustworthiness of banks. It’s not easy to isolate banking trustworthiness from customers’ propensity to trust–definitions are difficult. Two very different but powerful approaches to corporate trustworthiness measurement can be found in Trust Across America and in Laura Rittenhouse’s Rittenhouse Rankings of corporate candor.

4. An anti-trust ideology of business. We have inculcated a couple of generations of businesspeople with beliefs that drive down both propensity to trust and corporate trustworthiness.

Here are five ideologies in vogue since the 1970s:

a. Economists’ celebration of the virtues of markets–think Milton Friedman;

b. Strategists’ celebration of competition–think Michael Porter;

c. Pop philosophers’ celebration of laissez-faire systems–think Ayn Rand;

d. Financial theorists’ celebration of shareholder value–think Michael Jensen;

e. Government officials who embraced all the above ideologies–think Alan Greenspan.

If you doubt the power of beliefs to change society over a generation, consider this passage from Michael Lewis’s Vanity Fair article describing a German banker who was [recently] completely snookered by lying US investment bankers. Why was he taken? Lewis writes:

He mists up a bit when he tells stories about the Americans he did business with back then [in the early 80s]: in one story an American investment banker who had inadvertently shut him out of a deal hunts him down and hands him an envelope with 75 grand in it, because he hadn’t meant for the German bank to get stiffed.

“You have to understand,” he says emphatically, “this is where I get my view of Americans.”

In the past few years, he adds, that view has changed.

What does this add up to? It means:

- Low trust in business is not pre-ordained—we reap what we sow;

- Low trustworthiness drives low propensity to trust more than the other way around;

- Beliefs drive behaviors;

- Leaders’ belief systems exert big influence over trust in business.

What to Do?

If you’re with me on the diagnostic, there’s a simple prescription:

Leaders, Straighten Up and Think Right.

In other words: start with leaders and thoughts.

Here’s what Gallup has to say about how to build trust:

The effort to rebuild trust must begin with bank leadership, then flow through a bank’s employees to customers, the public, lawmakers, and regulators. Every interaction matters. If bank leaders and employees do not demonstrate that they trust their own bank, other stakeholders never will.

Because the process of rebuilding trust with the public starts with the bank, Gallup recommends that bank leaders make rebuilding employees’ trust in banks their No. 1 priority.

Yes, there’s more. Uslaner has a lot to say about economic inequality and education, and it’s very valuable. But you yourself—yes, you, the reader—may not have a lot of direct control over inequality. You do, however, control your own thoughts, and you probably influence and lead other people.

Start thinking trust-creation. When it comes to trust, thoughts have power.

I confess: I’m not one to read directions. Ever. But while hanging a mirror recently I happened to glance at the instructions on the back of the OOK package for picture wire (Will not fray! Will not rust!). I saw the best instructions ever:

I confess: I’m not one to read directions. Ever. But while hanging a mirror recently I happened to glance at the instructions on the back of the OOK package for picture wire (Will not fray! Will not rust!). I saw the best instructions ever:

I’d like some readers’ advice.

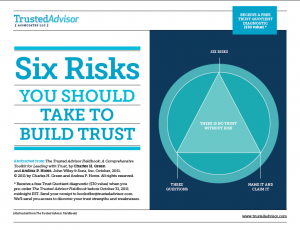

I’d like some readers’ advice. We’re pleased to announce the release of our latest eBook:

We’re pleased to announce the release of our latest eBook:  In honor of the US Labor Day holiday, we are not posting content today.

In honor of the US Labor Day holiday, we are not posting content today. A doctor, a lawyer and a rabbi all walk into a bar.

A doctor, a lawyer and a rabbi all walk into a bar. When it comes to trust-building, stories are a powerful tool for both learning and change. Our new

When it comes to trust-building, stories are a powerful tool for both learning and change. Our new  You think you’ve got it under control. Signed, sealed, all but delivered. You are in charge.

You think you’ve got it under control. Signed, sealed, all but delivered. You are in charge. In my

In my  When a child is untrustworthy, parenting is needed. When an adult is untrustworthy, counseling can help. When a company is untrustworthy, markets exact discipline.

When a child is untrustworthy, parenting is needed. When an adult is untrustworthy, counseling can help. When a company is untrustworthy, markets exact discipline. Have you ever sent out an email like this?

Have you ever sent out an email like this?