Trusted Transactions, or Trusted Relationships?

Justice Potter Stewart once remarked, with respect to pornography, that it was virtually impossible to define it, but, “I know it when I see it.”

Ditto for trust. It’s both a verb and a noun. Its objects are implied and contextual, as in “I trust my dog with my life – but not with my ham sandwich.”

Increasingly, we need to make explicit another dual-meaning of trust. We trust relationships, and we trust transactions. I trust John – to have my best interests at heart. I trust eBay – to create trustworthy transactions with strangers. It does not follow that I trust an eBay customer to go out on a date with my daughter.

Much of the public dialogue today confuses these two distinctions. Is it Congress that people don’t trust? Or is it members of Congress who themselves are considered untrustworthy? To the average voter, it’s a distinction without a difference. I suspect the inability to tease them apart is itself a source of anger. But if we fail to separate them, we doom ourselves not only to nasty public discourse, but to failed solutions.

Lessons from the 2007 Financial Crisis

Back in 1970, the US mortgage industry was still adequately described by the perennial Frank Capra Christmas movie “It’s a Wonderful Life,” with Jimmy Stewart as George Bailey, president of the Bedford Falls Savings & Loan. Bailey (for he and the company were inseparable) made loans to people he knew personally.

The bank’s depositors were Bailey’s friends and neighbors. The depositors were also the borrowers; likewise, the employees. The loans stayed on the S&L’s books, presumably to term. Those who took out mortgages had no intention of doing anything other than paying them off, with burn-the-mortgage parties at the end. No moral hazard here.

This was relationship trust. The strength lay in personal ties, cemented over time. A man’s word was his bond, and anyway you knew where he lived. His reputation was everything, at least until it wasn’t. Relationship trust served business and society well.

But relationship trust was about the only kind we had, and it had its limits.

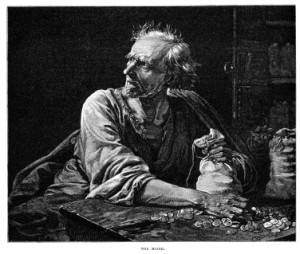

Transactional trust in George Bailey’s world was shallow and fragile indeed. The S&L was at risk of being forced out of business by a single competitor, the evil Mr. Potter. It was at risk of the low-tech deposit processes of Uncle Billy. Most importantly, it was at risk of a bank run. It was a good thing George Bailey worked the relationship trust game well, for he had precious little else to depend on.

Trusted Transactions in the Mortgage Business

Fast forward to 1995, Dwight Crane, Robert C. Merton and others published The Global Financial System: a Functional Perspective. A masterpiece of what sociologists knew as “functionalism,” this book laid out the case for transactional trust, viewing the mortgage business as one part of a complex and, ideally, integrated financial system.

In the chapter on mortgages, they ran down the characteristics of a system you could trust. It would have markets – markets for deposits, markets for mortgages, markets for loan originations. The book listed the costs of not having a systemically integrated system: risk of meltdowns, differential pricing within very narrow geographic regions, low liquidity, gross inefficiencies.

In short, George Bailey’s relationship-driven-trust was considered too risky, too costly, too uncreative and too unresponsive. Above all, it was too expensive. Consumers – the would-be purchasers of mortgages – were subjected to higher prices than necessary, driving up the cost of home ownership, and therefore driving down the economic livelihood of those seeking the American dream.

You simply could not trust such a system, the good professors opined. “It’s a Wonderful Life” was now half a century old. George Bailey was quaint. (No one noticed that only one year before the 1995 book, contributor Robert C. Merton had become a Board Member of the soon-to-be-notorious little hedge fund called Long-Term Capital Management L.P.)

In business, Progress was synonymous with all these terms: systemic, low-cost, efficient, market-based, liquidity. No one was about to cast doubt on the important and positive nature of all these terms. The academics and wunderkind of Wall Street were creating institutions you could trust.

The new trust was almost entirely cast in terms of systems and transactions. Transactions replaced relationships. Where markets couldn’t handle the job, models could. Of course, from today’s vantage point, this looks as naïve as the academics’ view of George Bailey a few decades ago.

In a few short decades, the “trust” pendulum swung from a man’s word to the solidity of a system. We went from high personal trust to high systemic trust – each extreme without the moderating influence of the other.

We Need Rich Trust

The transactional revolution in mortgage banking indeed delivered on most of its systemic promises. Markets were established, costs were lowered, liquidity was raised. But it all, as we know, ended very badly.

The confusion over trust went way beyond semantic. Alan Greenspan himself in 2008 famously said:

“I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in the firms.”

In other words, Greenspan thought that transactional trust would have the same sort of reputational bias that relationship trust had. He was, sadly for all of us, mistaken.

Transactional trust absent relationship trust had its own internal seeds of destruction. The absence of long-term relationships was crystallized in the Wall Street acronym IBGYBG – I’ll be gone, you’ll be gone, let’s do the deal. Just as personal trust doesn’t scale easily, so transactional trust doesn’t easily foster ethical behavior.

George Bailey wasn’t wrong, he just had no system. The professors weren’t wrong, they just assumed relationships. The truth is: we can’t afford just one form of trust or another, we need a rich mixture of both.

Well Beyond Mortgages

The mortgage industry is but one example. The electorate, reflecting it all, ends up exerting single-issue us-vs-them pressure on its own.

The polls are basically right: we do have a crisis of trust. But what crisis? It is not just a failure of morality. We cannot fix it solely by getting back to ‘family values,’ or seeking out leaders of impeccable morality. Those are, in fact, necessary conditions, but they’re not sufficient.

On the other hand, those who insist that the system is sound, it just needs tweaking, are dead wrong as well. This is not a matter of incentives needing adjustment. This is not a matter solely of transparency in markets. Those too are necessary conditions – but not sufficient.

We live in an interconnected world: transactional trust is critical for us to do live a life built on global commerce without it.

At the same time, there is no social structure or business process that can work without humans. There is no lock that can’t be picked, no code that can’t be broken. There is no inhuman system that can’t be perverted by humans.

Did anyone say Facebook? Uber? Airbnb? Zuckerberg and Sandberg today are as enamored of the potential for better algorithms to solve trust problems as Crane and Merton were about the potential of markets to unilaterally fix trust back in their day.

Trusted transactions? Or trusted relationships? Yes. We need ‘em both. Always have, always will.

In my

In my  Differentiation. It’s one of the

Differentiation. It’s one of the