When clients don’t buy what a CPA firm is selling, it’s unlikely that they don’t want what you’re selling. More likely it’s that they’re not buying how the service is being sold.

For example, a potential client is talking with several accounting firms about a significant assignment. One firm has expertise in that area and understands the client’s issues, and the meeting goes well. The firm bids competitively, recognizing the value of potential future work. The final presentation is a hit, but another firm gets the engagement.

The firm is surprised because the winning firm is not one that many in the business community would consider to be as competent. A week later, the firm asks the client for feedback. The client politely demurs, suggesting that the bid price may have been a bit out of line; maybe next time. The firm is puzzled, and concludes that things really are getting awfully competitive out there.

A month later, a partner of the firm accidentally (though legally) hears that the winning bid was 25% higher than the firm’s own bid. Some weeks later, the partner sees the would-have-been client at a golf course, and in that informal setting tells him of the new information, saying, “I can appreciate that perhaps you told me price was the issue to avoid a difficult conversation, but I would consider it a favor if you’d be truthful with me and help me understand what happened. It happens too often, and I don’t know why.”

The client assesses the CPA’s sincerity, and replies: “The truth is, there just wasn’t that sense of something—chemistry, trust, click, I don’t know what—that we had with the other firm. You had a fine track record and lots of good things to say. Your firm certainly has the credentials and clearly understands our business—but we just didn’t connect, we didn’t feel like you understand our company. You were eager to be helpful, but it was as if you were eager to be helpful for anyone—not just for us.”

The CPA firm partner asks, “What could we have done differently or better?” The client responds, “I don’t know. It’s just one of those things. You have to get your times at bat. But I think we’ll be seeing you again one of these days.” The partner leaves the golf course dumbfounded.

What the Problem Isn’t

David Maister, this author’s co-author on the book The Trusted Advisor, wrote in another book, Managing the Professional Services Firm (Free Press, 2004): “[T]he problem is never what the client said it was in the first meeting.” Accounting-firm clients, from CFOs to treasurers to comptrollers, have no trouble telling their CPA firm what they want.

Most professional services providers, such as lawyers, actuaries, and management consultants, are highly abstract, disciplined, analytical, structured, and unemotional. But accountants stand out within professional services on one dimension in particular: They are the most level-headed, “reasonable” professionals. Perhaps it has to do with the need to balance debits and credits, to cross-foot spreadsheets. It may involve the ubiquity of money: Not every issue is a legal, human resources, or information technology issue, but every issue must be financed or budgeted or has other financial impacts. Those qualities are the perfect characteristics for financial managers. Other managers in a company look to financial managers for permission to undertake initiatives; for guidance about what is reasonable; for parceling out resources and rewards; for evaluating whether things are going well; even for defining the very rules by which the rest of the company operates.

In general, such a person will strive to be clinical, removed, judicious, fair, analytical, detached, balanced, cautious, deductive, and will strive not to appear whimsical, passionate, partisan, emotional, confused, indecisive, erratic, or otherwise not in control.

How Financial Services Buyers Buy

Decisions like the one described above are typically made in two stages: screening and selection. The first stage is somewhat rational. Round up the usual suspects, throw in the chairman’s favorite, rate them objectively on criteria assessed by an assistant controller, then narrow down the field to three or so firms to be invited to submit bids and make presentations.

The CFO is likely to describe the selection process as being just as rational as the screening process, but the truth is otherwise. The personality traits of financial buyers show why such a person will want a process that is objective, data-based, defensible, analytical, and—above all—rational. The next-to-last thing the CFO wants is a wrong decision; the very last thing he wants is the appearance of a wrong decision.

This is how accounting firms end up being presented with questions like:

- Tell us why we should hire you.

- Tell us what is so different about your firm.

- Tell us how you would go about this work.

- Tell us about your credentials and references.

- Tell us what you know about our industry and our business.

And a firm being interviewed will generally be told things like:

- We want your best people on this.

- We need a very good price on this.

- Good value is very important to us.

Those are all rational questions and discussion points, from which one can draw comparatively different ratable and rankable answers, so they fit the analytical requirement for rational decision-making. More important, those questions are emotionally acceptable to the financial buying organization, people who want to see themselves and be seen by others as fitting the financial image.

The deeper truth will not be spoken aloud: The financial buyer really wants someone who makes him feel good about the decision. Someone he can trust, someone whose selection will allow him to sleep at night, someone he knows will go the extra mile, who can be depended upon to speak the truth, who knows the limits of his abilities and is not embarrassed to admit them when appropriate, someone who will behave appropriately in all circumstances, who knows how to finish his sentences, who treats his people the way the CFO treats his own staff, who “gets how things work here at XYZ”—and so on.

These are subjective qualities that defy objective rating or ranking and involve inferences and observations from interactions with the firm and its representatives, rather than responses to direct questions. In short, the financial buyer is trying to make an emotional decision that he can then comfortably rationalize.

What the Problem Is

Robert S. MacNamara, former U.S. Secretary of Defense, once said, speaking of politics, “Never answer the question you’re asked.” He may have been right in politics. In business, he’s only half right.

The selling accounting firm cannot avoid answering the question asked by the CFO—and the firm must also answer the questions that are unasked. Those questions cannot be answered directly, as in “You can really trust me to work well with your people” or variations thereof, because “Trust me” is about the least trustworthy thing one can say. Instead, the firm must demonstrate those qualities in how it sells itself.

Changing

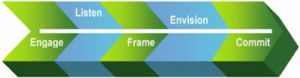

Principle 1: Sell by doing, not by telling. The most effective client relationships are those that have been around for a while. The firm and the client have gotten to know each other and the client has come to trust the firm. Because the best selling is virtually indistinguishable from doing, the CPA firm should design the sales process as much as possible as if it had already won the job.

The firm should build into the sales presentation how it would work with the client upon getting the job: engaging directly with the client as much as possible; talking openly and collaboratively about design and staffing alternatives; suggesting key issues to be decided; generally behaving with comfort and ease; having a conversation, not making a sales pitch.

A CPA firm that builds selling-by-doing into its sales process will become more open, transparent, and collaborative, precisely the behaviors that let the client assess trust, compatibility, “fit,” “chemistry,” and other intangibles.

Most clients set up sales processes to be distant, formal, and structured, and that must be respected. But within bounds, a CPA firm can suggest to clients that the selection process be more action-oriented. It is, after all, in the client’s interest to get the kind of freewheeling insights and ideas that come from open exchange.

Principle 2: Client focus without the vulture. Here is an exercise. A CPA dissociates herself from the winning or losing of a job, picturing herself in the future beyond the decision and feeling utterly indifferent about whether she won or lost.

She holds that thought, then asks herself, “What does this client really need, not just from this project, but in a much bigger context?”—without being limited by the request or her own service offering.

She now has some sense of what the client needs, but is not vested in winning or losing the job. She then returns her attention to the job at hand, picturing herself calmly advising the client about what needs to be done, and how, and when, and with what approach and resources, moving the client forward in the larger direction of what needs to be done.

Those who can honestly speak the truth about what needs to be done, without attachment to winning and losing, will convey the biggest emotional truth to the client: They will convey that they care about the client. This—focusing on the client’s needs for the sake of the client—differs from the usual kind of client focus that is the focus of a vulture: Focus for the seller’s sake, not the client’s.

Of the factors driving trust—credibility, reliability, security—none ranks higher than this sense of the seller’s being able to put the client’s needs ahead of his own need to “get the deal.” And here the paradox of trust kicks in: Truly separating from the need to win enhances one’s chances of winning.

As with many apparently either/or questions, this one is best answered by defining our terms. Client feedback is indeed critical—but how you get it varies radically by what you are trying to find out.

Most salespeople will agree—there is no stronger sales driver than a customer’s trust in the salesperson. Further, the most successful route to being trusted is to be trustworthy—worthy of trust. Faking trust is not easy—and the consequences of failing at it are large.

Most salespeople will agree—there is no stronger sales driver than a customer’s trust in the salesperson. Further, the most successful route to being trusted is to be trustworthy—worthy of trust. Faking trust is not easy—and the consequences of failing at it are large.

The way most of us would view having to handle snakes.

The way most of us would view having to handle snakes.

“I want you to advise me in this area,” they say. “I’ll do whatever you tell me to do.” And you know that they will.

“I want you to advise me in this area,” they say. “I’ll do whatever you tell me to do.” And you know that they will.