But is it possible to know if your client does trust you? Is there one predictor of client trust? Is there a single factor that amounts to an acid test of trust in selling?

I think there is. It’s contained in one single question. A “yes” answer will strongly suggest your customers trust you. A “no” answer will virtually guarantee they don’t.

The Acid Test of Trust in Selling

The question is this:

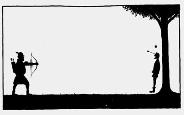

Have you ever recommended a competitor to one of your better clients?

If the answer is “yes”—subject to the caveats below—then you have demonstrably put your customer’s short-term interests ahead of your own. This indicates low self-orientation and a long-term perspective on your part (I’m assuming sincerity), and is a good indicator of trustworthiness.

If you have never, ever, recommended a competitor to a good client, then either your product is always better than the competition for every customer in every situation (puh-leeze), or—far more likely—you always shade your answers to suit your own advantage. Which says you always put your interests ahead of your customers’. Which says, frankly, you can’t be trusted.

Here are the caveats: don’t count “yes” answers if:

a. The client was trivially important to you

b. You were going to lose the client anyway

c. You don’t have a viable service offering in the category

d. You figured the competitor’s offering was terrible and you’d deep-six them by recommending them.

The only fair “yes” answer is one in which you honestly felt that an important clientwould be better served in an important case by going with a competitor’s offering.

If that describes what you did, and it is a fair reflection of how you think about client relationships in general, then I suspect your clients trust you.

This is the “acid test” of trust in selling. To understand why it’s so powerful, let’s consider the factors of trust.

Why Is This the Acid Test?

My co-authors and I suggested in The Trusted Advisor that trust has four components, and we arrayed them in the “trust equation.” More precisely, it is an equation for trustworthiness, and it is written:

T = (C R I) / S

where:

T = trustworthiness of the seller (as perceived by the buyer),

C = credibility,

R = reliability,

I = intimacy, and

S = self-orientation.

Credibility is probably the most commonly thought-of trust component, but it is only one. Think of credibility and reliability as being the “rational” parts of trust. Believable, credentialed, dependable, having a track record—these are the traits we most consciously look for in screening for vendors, doctors, and websites.

The third factor in the numerator—intimacy—is more emotional. It has to do with the sense of security we get in sharing information with someone. We say we “trust” someone when we open up to them, share parts of ourselves with them. We trust those to whom we entrust our secrets.

But all pale beside the power of the single factor in the denominator—self-orientation. If the seller—the one who would be trusted, who strives to be perceived as trustworthy—is perceived as being self-oriented, then we see him as in it for himself. And that’s the kiss of death for trust.

At its simplest, high self-orientation is selfishness; at its most complex, self-absorption. Neither gives the buyer a sense that the seller cares about any interests but his own.

Self-orientation speaks to motives. If one’s motives are suspect, then everything else is cast in a different light. What looked like credible credentials may be a forged resume and false testimonials. What looked like a reliable track record may be an assemblage of falsehoods. What looked like safe intimacy may be the tactics of a con man. Bad motives taint every other aspect of trust.

The acid test aims squarely at this issue of orientation. Whom are you serving? If the answer is, the client, then all is well. No client expects a professional to go out of business serving them; the need to make a good profit is easily accepted.

It’s when the need to run a profitable business is given primacy in every transaction, every quarter, every sale, that clients call your motives into question. How can they trust someone who’s never willing to invest in the longer term, never willing to compromise, never willing to do gracefully defer in the face of what is best for the client? They cannot, of course.

Passing the acid test suggests you know how to focus on relationships, not transactions; medium and long-term timeframes, not just short-term; and collaborative, not competitive, work patterns.

Flunking the acid test means clients doubt your motives. Whether you are selfish or self-obsessed makes little difference to them—the results are self-aggrandizing, not client-helpful.

The paradox is: in the long-run, self-focused behavior is less successful than is client-helpful behavior. Collaboration beats competition. Trust beats suspicion. Profits flow most not to those who crave them, but to those who accept them gracefully as an outcome of client service.