Robert Eccles is a Professor of Management Practice at the Harvard Business School. For over three decades he’s been active in management accountability—linked to, but not limited to, more traditional concepts of financial-only reporting. He’s written several books before, perhaps most notably Building Public Trust: The Future of Corporate Reporting with Sam DiPiazza, former Global CEO of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), but he may have finally hit a new level of interest with the arrival of his book One Report: Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Strategy.

Bob speaks to us here a few months following a 100-person “Workshop on Integrated Reporting: Frameworks and Action Plan” sponsored by the school’s Business and Environment Initiative. You can download a free ebook from the event, The Landscape of Integrated Reporting: Reflections and Next Steps, with papers by about half the participants—it’s excellent.

Charlie Green: First, thanks very much for speaking with us. I first became aware of you from your work with Sam DiPiazza, but you’ve been working in performance measurement and reporting since long before that.

Might we say your expertise is the measurement and management of diverse indicators of corporate performance? How shall we call what it is that you do?

Robert Eccles: I’d say that I’m deeply interested in corporate performance measurement and reporting, with an emphasis on external reporting—a powerful lever for changing behavior and decision making by executives.

CHG: How did you get into this field?

RE: It goes back to my undergraduate thesis at MIT, but we needn’t go back that far! I was an Assistant Professor at HBS when I wrote a book on transfer pricing. After I became tenured in 1989, I started writing cases for a new first year course called “Information, Organization and Control.” I found companies getting interested in performance measures beyond the traditional financial ones.

Based on this I wrote a 1991 HBR article, with Sarah Mavrinac, called “The Performance Measurement Manifesto.” One year later Bob Kaplan published his famous article on the Balanced Scorecard, another indicator of interest in this topic. We both were focused on internal measurement. Bob remains so to this day, but I got interested in what companies were reporting and what information sell-side analysts and investors wanted from them.

This led to a 1995 Sloan Management Review article called “Improving the Corporate Disclosure Process.”

I left HBS to work in the private sector and this included researching and improving corporate reporting. I wrote The ValueReporting Revolution: Moving Beyond the Earnings Game with three PwC partners, including Bob Herz, recently retired as Chairman of the Financial Accounting Standards Board. I returned to HBS in 2007 and wrote One Report which was published in early 2010.

CHG: I’ve been aware for some time of movements like the Balanced Scorecard to integrate non-purely-financial metrics into the rubric of reporting. But I hadn’t heard of Integrated Reporting until just recently. How old is that term?

RE: Good question—I’m not really sure. Allen White used the term in 2005 in a piece for Business for Social Responsibility. That same year Solstice Sustainability Works wrote a white paper called “Integrated Reporting: Issues and implications for Reporters.” But even though Novo Nordisk has been publishing an integrated report since 2004, and Novozymes two years before that, those articles went unnoticed. The times just weren’t ready.

In March, 2010, about the same time my book was published, Southwest Airlines came out with their “Southwest Airlines One Report™.” Neither of us knew about each other’s initiatives until the summer of that year. I think the times are catching up.

CHG: What is Integrated Reporting? How do you define it?

RE: First of all, the term is still gaining acceptance so there is no general agreement on its meaning. Here’s my most basic answer. It is the publication in a single document of the material measures of financial and non-financial performance and the relationships between them.

It also involves leveraging the Internet and the company’s website to provide more detailed financial and non-financial information of interest to particular stakeholders, including shareholders, along with tools for analyzing this information. Finally, it’s about increasing dialogue and engagement with all stakeholders. It’s as much about listening as it is talking.

CHG: That begins to explain the connection with trust.

RE: Right—among other things, it’s about building trust between a company and its stakeholders. This trust comes from being transparent about all dimensions of performance—successes and shortcomings—and from active dialogue and engagement. For stakeholders to have trust, they need to know their expectations and concerns are being heard and that the company is honestly and forthrightly reporting on the meeting of expectations.

Of course, trust is a two-way street. Companies can’t optimize on every performance dimension, especially over short periods of time. Trade-offs are involved and must be accepted. Shareholders need to recognize the legitimate interests of other stakeholders; ditto for stakeholders and the need for companies to make financial returns.

Risk is relevant to trust too. Creating shareholder value requires risk taking. What’s required are candor about risk levels, systems and processes for risk management, and communication about the approach to risk management. Ultimately, risk management is about good corporate governance.

The “G” part of “ESG” (Environment, Social, Governance) typically gets less attention that the “E” and “S” part, because it’s harder to measure. But that doesn’t make it less important. What happens when they’re all missing? Consider big financial institutions in the meltdown of late 2008. Or BP in the Gulf of Mexico.

CHG: If the world had a robust system of Integrated Reporting—what would we have? What are the benefits, what’s the business case (or socio-business case?) for Integrated Reporting?

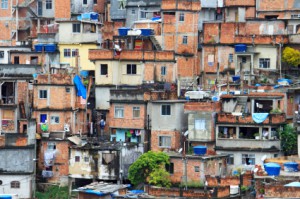

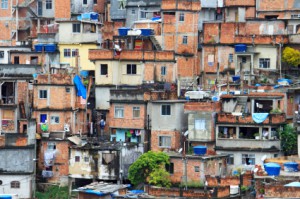

RE: The greatest benefit would be a sustainable society—able to meet the needs of a growing number of citizens all over the world, mostly from developing countries, while still being able to meet the needs of future generations. Neither developing nor developed countries can continue consuming natural resources at today’s rate, creating negative environmental and social externalities, and practicing poor risk management and corporate governance.

RE: The greatest benefit would be a sustainable society—able to meet the needs of a growing number of citizens all over the world, mostly from developing countries, while still being able to meet the needs of future generations. Neither developing nor developed countries can continue consuming natural resources at today’s rate, creating negative environmental and social externalities, and practicing poor risk management and corporate governance.

CHG: But certainly reporting can’t fix that by itself?

RE: No, certainly not. Management practices, technologies, intelligent regulation and individual decisions play an important role as well. But Integrated Reporting is central, because reporting is a major determinant of behavior. It establishes discipline for the integrated management of financial, natural and human resources. It meets stakeholders’ information needs, along with processes of engagement, to help them help the company build a sustainable strategy. A sustainable society requires that all of its companies have a sustainable strategy. Integrated Reporting is central to this.

CHG: I get the sense that recently, things have changed a bit. Is this perhaps an idea whose time has finally come? Are you still feeling quixotic, or are there some genuine causes for optimism?

RE: “Quixotic” is a good choice of words. I have been working at this for over 20 years now and I can relate to Don Quixote tilting at those windmills. But today I feel extremely optimistic. First, companies have started to do it. They came to this largely on their own, and for pretty much the same reasons. No one had written a book and the topic was still fairly obscure.

Prince Charles started his UK-based “Accounting for Sustainability Project (A4S)” a few years ago. Starting June 1 of 2010 all Johannesburg Stock Exchange listees must file an integrated report as their annual report. France and others have passed similar laws, and it’s being considered by the entire European Union.

In August of 2010 the International Integrated Reporting Committee (IIRC) was formed. The Secretariat of this group is A4S and the Global Reporting Initiative. On its Steering Committee (of which I am a member and we had our most recent meeting in Beijing on January 17) and Working Group are prominent experts on corporate reporting from many different disciplines, and from all over the world. We hope to get Integrated Reporting on the agenda of the G20 meeting being hosted by France in November 2011.

Momentum for Integrated Reporting—driven by both market and regulatory forces—is growing and growing rapidly.

CHG: Dean Nohria at Harvard Business School recently opened up your conference with some very clear and strong language about the critical nature of trust to business. You know Nohria personally, but let me ask you institutionally as well: what does it mean for the Dean of Harvard Business School to be talking trust?

RE: I can’t tell you how significant I think it is that our new Dean is talking about trust. Though he’s a close personal friend of mine, I think I can objectively say that he is a man of the highest integrity and with a strong belief of the good business can do in society. The fact that his opening remarks at the HBS workshop on Integrated Reporting you mentioned at the beginning of this interview were focused on the need for business to rebuild trust in society pretty much says it all. His opening remarks are the basis of the introduction he wrote for the EBook and I would encourage all the readers of your blog to read what he had to say.

CHG: I’ve noticed a continued effort on the part of most people in arena of ESG (environmental, social and government issues) to try and justify their work in financial terms. At least one says that’s because business will never listen unless they can clearly see the profit value tightly demonstrated. But the tighter the justification in corporate profits, the less powerful the argument for a non-profit-based accounting, much less ethos, don’t you think? What’s the right way to think about Integrated Reporting and corporate profitability?

RE: I would frame this a little differently. I don’t think the issue is profits per se. Every corporation with shareholders needs to make a profit if it is going to stay in business. Rather, the issue is how those profits are earned, what social and environmental costs are created in earning them, how much risk is being taken and how well it is being managed, and the time frame management is using in making its decisions. The latter is a key issue. A focus on short-term profit maximization and ignoring all negative externalities and excessive risk as long as the letter of the law is being followed does not lead to a sustainable strategy for a company. If most companies have a short-term orientation, and the capital markets are as much at fault as the companies are, we will not have a sustainable society.

The fundamental issue—raised but not answered by integrated reporting itself—is “What is the role of the corporation in society?” There were some very thoughtful pieces on this topic written by some of the HBS workshop participants. Society as a whole needs a big rethink about what it expects out of its corporations, especially the largest global ones that control so much and have such impact on resources.

We need to develop a collective understanding about how companies identify the needs of all stakeholders, the processes they should use to make decisions regarding performance targets and performance trade-offs, and the time frame involved.

What I’m talking about is a massive societal undertaking. But until it happens, trust in business will remain fragile, and easily lost every time we go through a crisis, even when the fault is not business’s alone.

CHG: What role can education play in helping improve trust in business? Is this mainly a role for MBA programs? Or can other programs play a useful role as well?

RE: Business schools can play a role in helping students understand society’s expectations about them as stewards of social assets. This goes beyond “ethics” (I will ignore the age-old question of whether ethics can be taught to 20-somethings if they haven’t already learned them from parents, churches and communities) and gets at the fundamental issue of the role of the corporation in society.

This topic should be part of every business school curriculum, undergraduate or MBA. It will require directly challenging the prevailing view based on financial economic theory in the western world. One hundred years ago “shareholder primacy” was not the prevailing ideology; there is no reason to think that it will or should be in 100, or even 10 years from now, particular since the concept of “shareholder” has become so loose in an age of hedge funds, technical trading programs and relatively short-term holdings by mutual funds and even pension funds.

But remember, trust is a two-way street. Citizens need a basic understanding of the social role of business, how companies work, and the trade-offs they have to make. They must commit themselves to engage as employees, customers, shareholders, and members of civil society. Too often other programs (such as in the liberal arts, engineering, science, architecture, law, and medicine) include nothing about business in their curriculum even though all of these groups are dependent on and must work with business organizations. It’s no surprise they are often hostile to business.

Hostility is not a good foundation for trust. It’s good to be skeptical, but in a constructive spirit with a desire to build trust, not to destroy it.

CHG: What’s the biggest implementation challenge facing Integrated Reporting? And what do you think is the biggest challenge to trust creation in the business world? Do those two overlap?

RE: Challenges exist at the level of individual companies, and of society. I see four major corporate challenges.

1. A company must truly have a sustainable strategy, not just say it has, which is more often the case.

2. The process for producing an Integrated Report must itself be collaborative and multifunctional.

3. Internal control and measurement systems for non-financial information are typically not as sophisticated and robust as those for financial information.

4. Internal skeptics need to be persuaded. Executives need to accept that greater responsibility will entail greater accountability and, when they fail, they will pay the consequences—just as they do with financial performance. Users, both shareholders and other stakeholders, will require a lot of education.

At the level of society as a whole, Integrated Reporting is a necessary but not sufficient condition for creating a sustainable society; that’s a giant collective action problem. Companies are the entities doing the reporting and so they clearly can and should take the lead. After all, no country has any laws preventing Integrated Reporting.

But for Integrated Reporting to be as effective as possible, other groups need to get involved too. Measurement and reporting standards for non-financial information need to be developed so that analysts and investors have confidence in them and can compare the performance of companies, at least within a sector, and over time. These analysts and investors must then incorporate those measures into their financial models, turning them into business models.

Accounting firms need to develop the methodologies and capabilities for doing integrated audits. This may require some liability protection from legislatures and regulators, who also have a codification and specification role to play. NGOs need to collaboratively engage with companies to make the processes work. They also need to take a more holistic view themselves. Educators also have a role, as I’ve already discussed.

Finally, every member of civil society—and that is each and every one of us—needs to commit to a sustainable society and to do whatever he or she can to support the Integrated Reporting social movement. We only have one planet and we’re all in this together. If we don’t work together for the long term, we’ll have no long term.

CHG: This sort of brings us full circle, does it not?

RE: Yes; both Integrated Reporting and trust are about transparency, accountability and engagement. As companies practice it, they will gain trust from stakeholders. Society-level efforts will also help build trust from the shared vision, commitment and understanding that emerges between all groups.

And, as I’ve said, ultimately effective Integrated Reporting and trust in business by society requires a new view and consensus of the role of the corporation in society.

CHG: Bob, thanks again very much for taking this time with us, it’s been fascinating.

—————————————————

Robert Eccles on Integrated Reporting is number 18 in the Trust Quotes: Interviews with Experts in Trust series.

The latest case in point: Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) Chairman James R. Doty, keynoting on the subject of Integrity at the Seventh Annual Auditing Conference:

The latest case in point: Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) Chairman James R. Doty, keynoting on the subject of Integrity at the Seventh Annual Auditing Conference:

RE: The greatest benefit would be a sustainable society—able to meet the needs of a growing number of citizens all over the world, mostly from developing countries, while still being able to meet the needs of future generations. Neither developing nor developed countries can continue consuming natural resources at today’s rate, creating negative environmental and social externalities, and practicing poor risk management and corporate governance.

RE: The greatest benefit would be a sustainable society—able to meet the needs of a growing number of citizens all over the world, mostly from developing countries, while still being able to meet the needs of future generations. Neither developing nor developed countries can continue consuming natural resources at today’s rate, creating negative environmental and social externalities, and practicing poor risk management and corporate governance. Regarding regulation beyond our domestic borders: because there is no global government system, a truly global regulatory structure is unlikely in the foreseeable future. Differences among geographies in this increasingly global economy are inevitable. It’s natural for countries to want to reserve the right to do what they believe is in their best interest given the unique circumstances of their nation.

Regarding regulation beyond our domestic borders: because there is no global government system, a truly global regulatory structure is unlikely in the foreseeable future. Differences among geographies in this increasingly global economy are inevitable. It’s natural for countries to want to reserve the right to do what they believe is in their best interest given the unique circumstances of their nation.